Waiting for Marriage: How a Patriarchal Status Quo is Reinforced Through Sexual Controls

Waiting for Marriage:

How a Patriarchal Status Quo is Reinforced Through Sexual Controls

By Pranathi Adhikari

A daughter’s eligibility to marry is earned in adolescence by conforming to patriarchal social expectations set in their youth—expectations which control and suppress women. In many places around the world, young women and girls face severe repercussions for a range of infractions that constitute a perceived misuse of their sexuality. Such infractions include inappropriate interactions with members of the opposite sex, wearing revealing clothing, and engaging in premarital sexual activity.[i] Given this range, any socially constructed perception of a girl’s sexuality can affect her marriageability. In effect, a woman is ostracized from society, tainting family honor. Thus, the family also faces pressure to uphold their status through their daughters, in some cases, through honor killings.[ii]

This social expectation for a girl to preserve herself serves a dual purpose: to perpetuate sexual constrictions and ensure the longevity of a patriarchal status quo. By this virtue, actions of empowerment may call for punishment. In India, an “elevated sense of vindication and righteousness” has been cited as a cause for honor killing.[iii] Second, by emphasizing marriageability as a pillar of womanhood, women are limited to that role in society. In a variety of cultures, men exercise control over women’s sexualities by delineating sexual independence as a threat to this pillar. Two clear cases in which sexual controls are imposed over young girls are in India and Jordan, where the gendered status quo is reinforced and preserved by social punishments and future marriageability as a reward.

The Perceived Cost of Daughters in India

India serves as an example of where there has been a documented decline in the child sex ratio at birth, which demonstrates that boys are favored over girls.[iv] This imbalance is further demonstrated by the rates of female foeticide and infanticide that are prevalent in parts of India. In 2002, India passed the Prohibition of Sex Selection Act, which outlawed the termination of a fetus on account of its sex.[v] However, as of the 2011 Indian census, an estimated 2.5 million girls were missing on account of prenatal discrimination.[vi] While the child sex ratio is lower in some states than in others, the issue of discrimination against female infants transcends class and geographic region. In one instance, the wife of a senior executive in a multinational corporation terminated 8 pregnancies before dying while delivering a son.[vii]

Infanticide is the killing of a dependent child under the age of one by someone is entrusted with their care.[viii] In India, a high prevalence of female infanticide has also been reported from a “female infanticide belt,” which extends through the Tamil Nadu state in southern India.[ix] While female infanticide was cited to be more likely in single-caste communities, slow killing from neglect and discrimination is a growing issue in multi-caste communities.[x] According to the 2011 census, an estimated 1.5 million girls were reported missing in India due to infanticide.[xi]

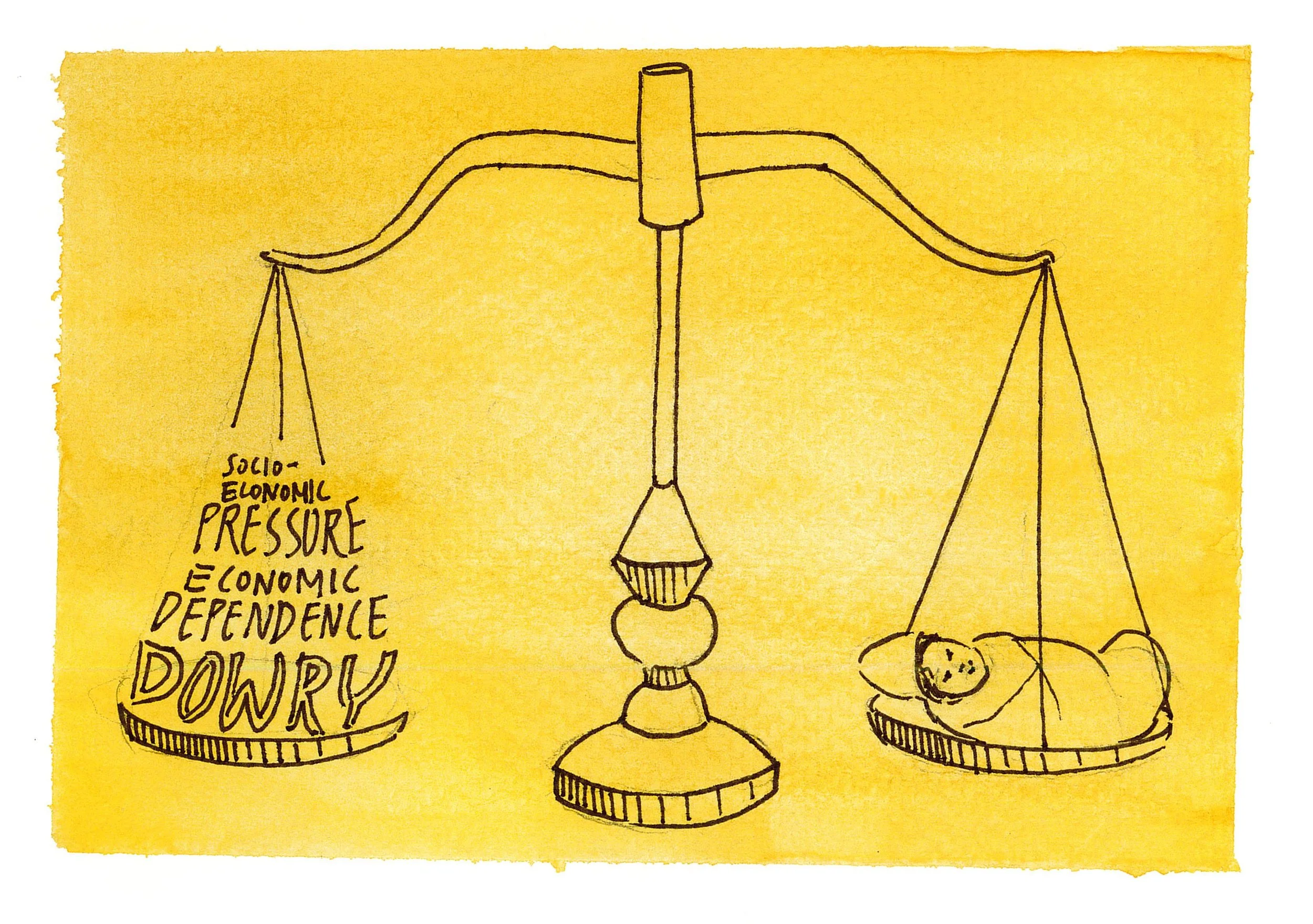

Though cases of female foeticide and infanticide are indiscriminate to economic class, geographical region, and caste, other factors such as poverty, dowry, and economic dependence all contribute to the socio-economic pressure on lower caste communities to commit foeticide or infancide selectively against female children.[xii][xiii] In these cases, girls are considered a financial loss for families. For families living in poverty, an additional investment on a child may strain family expenses. Furthermore, a female child who would not carry on a family name or earn a living may feel seemingly unnecessary.[xiv] In addition, a practice of dowry forces a family to pay the husband’s family to take their daughter as a wife.[xv] The combined cultural and socio-economic factors play into the pressure to continue selective sex practices in India.

The Issue of Marriageability

Many girls are born into a cultural context in which they are discriminated against at birth and throughout their youth. As teenagers, this socializes them “to accept a position subservient to males, to control their sexual impulses, and to subordinate their personal preferences to the needs of the family and kin group.”[xvi] In order to fulfill this position, these young women bear the forced responsibility to maintain their marriability for the sake of themselves and their families. As such, they meet the expectation for marriageability by conforming to social expectations to protect their virginities and navigate conservatively through society. Such is the case in Jordan and India, where this reimposes sexual control and a gendered status quo that discriminates against young girls. The consequences of disobeying this social norm can cost a girl her marriageability.

In one instance, a pair of girls in Badaun, India were found hanging by a mango tree after disappearing to use the bathroom the night before. The complexity lay in the fact that the girls, Padma and Lalli, were discovered to have been in contact with a boy from a nearby town in the time leading up to their deaths. Investigations later concluded that Padma had engaged in sexual intercourse with this boy leading up to her death. But the mystery lay in how or why the girls had died—was it for the fragility of the family’s honor?

Even so much as the discovery of Padma or Lalli engaging in forbidden interaction with a boy threatened the honor of their family. In Jordan, any suspicion of premarital sexual activity can also have a similar consequence. In the Badaun case, not only would it ostracize them from their community and dishonor their family, but the news would also make it nearly impossible to find a suitable husband. Aware of these consequences, the girls sacrificed their own lives for the honor of the family. Had the girls not taken their own lives, the burden to restore the family’s honor would have rested on the family.[xvii]

Avenging Honor in India and Jordan

While the cultural and economic significance of marriageability is not static across all cultures, India is only one example of where a daughter’s sexuality is put under scrutiny. For example, traditional Jordanian culture also scrutinizes the sexuality of girls when it comes to marriageability.[xviii] In both examples, honor killing may be committed against teenage girls who engage in sexual intimacy outside of marriage, regardless of whether or not the sexual act was consensual. This tradition is discriminatory against women, many of whom are punished for crimes of sexual promiscuity while culpable men walk away freely, even in the event of rape. Honor killings are a social control to avenge family honor when marriageability is tainted. One study conducted on ninth graders in Jordan found that about 40% of boys and 20% of girls believed that honor killing could be justified.[xix] Thus, the acceptance of justification for honor killings ultimately reduces to a communal understanding that girls play the role of wife in society.[xx]

Depending on the reporting organization, global estimates suggest that anywhere from 5,000 to 20,000 honor killings occur annually, not only exemplifying this global problem, but also the larger attempt to maintain a status quo by exerting control over women’s sexuality.[xxi] These broad estimates suggest a lack of initiative by governments to track this problem. For example, family members often report honor killings as suicide or homicide, and all evidence is destroyed for the sake of immediate cremation. Since there is no specific legal clause requiring that honor killings be investigated as such, its occurrence is difficult to track.[xxii] Similarly, honor killings can be guarded by legal codes as in Jordan, where the law states that murder is permissible in the event that the killing is done in defense of one’s self, one’s honor, or someone else’s life or honor. By this codified definition, honor killing on the basis of perceived misuse of sexuality is justified. Not only this, but the law also justifies honor killing by the family or anyone else seeking to defend the family’s honor on their behalf.[xxiii] Virginity is treated as a commodity which belongs to men, guarded by a network of family and community members.

Implications

Despite cultural differences in the significance of marriageability around the world, it still functions as a reward earned by young girls for obeying social expectations. Often, marriageability is contingent on ones virginity and obedience towards other social taboos in regards to sex, such as clothing and male relationships. In this way, the threat of losing marriageability restricts a girl’s sexual freedom, minimizing her role in society to “wife.” This social punishment is difficult to bear, as it brings shame to the family, making it hard to escape on more levels than one. As such, a sexual control over women reinforces a status quo in favor of a traditional patriarchy.

Illustration by Esther Wang

[i]. Moghadam, Valentine M. “Patriarchy in Transition: Women and the Changing Family in the Middle East.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 35, no. 2 (2004): 143.

[ii]. Moghadam, “Patriarchy in Transition,” 143.

[iii]. D’Lima, Tanya, Jennifer L. Solotaroff, and Rohini Prabha Pande. “For the Sake of Family and Tradition: Honour Killings in India and Pakistan.” ANTYAJAA: Indian Journal of Women and Social Change 5, no. 1 (June 1, 2020): 30. https://doi.org/10.1177/2455632719880852.

[iv]. UNFPA, “Missing: Mapping the Adverse Child Sex Ratio in India.” UNFPA (2019): 23.

[v]. UNFPA, “Missing: Mapping the Adverse Child Sex Ratio in India,” 24.

[vi]. Kulkarni, Purushottam M. “Sex Ratio at Birth in India- Recent Trends and Patterns,” UNFPA (2020): 43.

[vii] UNFPA, “Missing: Mapping the Adverse Child Sex Ratio in India,” 25.

[viii]. Tandon, Sneh Lata, and Renu Sharma. “Female Foeticide and Infanticide in India: An Analysis of Crimes against Girl Children” 1, no. 1 (2006): 3.

[ix]. Chunkath, Sheela Rani, and V. B. Athreya. “Female Infanticide in Tamil Nadu: Some Evidence.” Economic and Political Weekly 32, no. 17 (1997): WS22.

[x]. Tandon and Sharma, “Female Foeticide and Infanticide in India: An Analysis of Crimes against Girl Children,” 4.

[xi]. Kulkarni, Purushottam M. “Sex Ratio at Birth in India- Recent Trends and Patterns,” 43.

[xii]. UNFPA, “Missing: Mapping the Adverse Child Sex Ratio in India,” 25.

[xiii]. Tandon and Sharma, “Female Foeticide and Infanticide in India: An Analysis of Crimes against Girl Children,” 4.

[xiv]. UNFPA, “Missing: Mapping the Adverse Child Sex Ratio in India.” UNFPA (2019): 3.

[xv]. UNODC, “Global Study on Homicide 2019.” UNODC (2019): 23.

[xvi]. Avasthi, Ajit. “Preserve and Strengthen Family to Promote Mental Health.” Indian Journal of Psychiatry 52, no. 2 (2010): 113–26. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.64582.

[xvii]. Faleiro Sonia, The Good Girls: An Ordinary Killing (New York, Grove Press, 2021): 1-314.

[xviii]. Ruggi, Suzanne. “Commodifying Honor in Female Sexuality: Honor Killings in Palestine.” Middle East Report, no. 206 (1998): 12–15. https://doi.org/10.2307/3012473.

[xix] Eisner, Manuel, and Lana Ghuneim. “Honor Killing Attitudes Amongst Adolescents in Amman, Jordan.” Aggressive Behavior 39, no. 5 (2013): 405. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21485.

[xx]. Ruggi, “Commodifying Honor in Female Sexuality,” 13.

[xxi]. D’Lima, Solotaroff, and Pande, “For the Sake of Family and Tradition,” 22.

[xxii]. Swaddle, The. “Why a Separate Law for Honor Killings Is the Need of the Hour.” The Swaddle (blog), April 21, 2020. https://theswaddle.com/honor-killings-india-law/.

[xxiii]. Ruggi, “Commodifying Honor in Female Sexuality,” 13.