Kids These Days: The Links Between Reform and Young World Leaders

Kids These Days:

The Links Between Reform and Young World Leaders

By Michael Dekhtyar

Introduction

Are younger government leaders inherently more reformist ones? The question is an intriguing one, and at first glance has a clear answer—of course they are! Young political leaders and activists like Greta Thunberg and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez are among the most well-known and impactful political figures of our time. Going from headlines alone, it would be easy to conclude that youth is closely linked to “progressivism” in the context of a country’s unique political, social, and economic circumstances. Yet the reality is far more complex (and sometimes contradictory) than that; after all, the 78-year-old US president Joe Biden is leading what may end up being the most progressive administration in decades (bolstered by the recent passage of a historic infrastructure investment bill), while the 67-year-old Belarussian president Alexander Lukashenko has overseen widespread human rights abuses and violations of civil liberties in the face of mass protests across the country.[i] By contrast, in Austria, the conservative politician Sebastian Kurz, who was elected at age 31, remained the youngest head of state in the world for four years until his recent replacement by the 52-year-old career diplomat Alexander Schallenberg.

Is there a definitive link between the relative youth of government leaders around the world and the degree of reform and progress that their administrations pursue? Two regions of the world have recently chosen relatively young leaders—Volodymyr Zelensky in Ukraine and Abiy Ahmed in Ethiopia. Studying these figures’ approaches to governance provides a clearer picture of the links (or lack thereof) between the young age of political leaders and the degree of progressive reform they end up supporting.

Ukraine

Ukraine’s experiences with the promises and pitfalls of economic and political change give considerable insight into the relationship between the youth of world leaders and the degree of “reformism” that defines their times in office. The current Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, was elected in 2019 with an overwhelming 73.2% of the vote, gaining a widespread national mandate for his strong anti-corruption policies and broader reform-focused agenda. Zelensky’s campaign was launched to victory by his popular approach to fair and equitable governance, which placed renewed emphasis on improving well-being for all Ukrainians and taking a harder line against corrupt institutions, organizations, and individuals. Corruption is one of Ukraine’s most notable political issues and remains at the forefront of almost all voters’ priorities, allowing Zelensky’s strong anti-corruption stance to be the defining characteristic of his ultimately successful reform-focused campaign.

The first months of Zelensky’s presidency were promising in the context of anticipated reform and progress. He introduced several comprehensive reforms aimed at combating corruption: abolishing immunity for members of the Ukrainian parliament, establishing criminal liability for illegal personal enrichment, and creating a new Supreme Anti-Corruption Court to focus exclusively on high-profile corruption cases (which lessened the massive backlog of cases in Ukraine’s existing court system).[ii] In addition, Zelensky proposed drastic reforms to Ukraine’s electoral system, introducing a new proportional representation system to better reflect public support for political parties while lowering the entry threshold for new parties into the national parliament from five percent to three percent of the popular vote.[iii]

However, Zelensky’s dynamic and youthful image has not translated to effective governance or widespread success in his anti-corruption efforts. The president’s proposed electoral reforms were all rejected or considerably weakened by the country’s parliament, while his widely-touted campaign to clean up the finances of the government and the national economy appears to have come to a screeching halt amid political infighting and instability.[iv][v] Frustration with the young president’s relatively disappointing time in office is increasingly obvious among the Ukrainian population. Just over a year after taking office, Zelensky’s approval rating plummeted from 71% to 38% (though those numbers have recently improved somewhat), and his failure to deliver on crucial reforms seems to be the root cause.[vi] A report by the Brookings Institute summarizes that “[Zelensky] has fired a reformist prime minister and cabinet, replaced a prosecutor general who had begun weeding out bad eggs among prosecutors, and triggered the resignation of a National Bank of Ukraine head who had won plaudits for steering an independent course.”[vii] This seems to be the latest iteration of a familiar theme in Ukrainian politics: progressive presidential candidates take office on an anti-corruption ticket and launch several promising initiatives to clean up the country’s finances and politics, but end up failing to achieve any lasting reforms—leaving a disillusioned country in their wake.[viii]

Furthermore, Zelensky’s involvement in the damning details of the Pandora Papers has only reinforced the public perception that he is incapable of challenging the chokehold on economic, legal, and political power held by the country’s oligarchs. The Papers—a massive trove of nearly 12 million leaked documents that detail the secret financial dealings and practices of government officials, political leaders, and wealthy individuals all over the world—reported that Zelensky and several of his close allies secretly own and operate several offshore real estate companies in the Virgin Islands, Belize, and Cyprus.[ix] This does not necessarily mean he is guilty of the same corruption and excess that he promised to fight against during his campaign, but it does not bode well for an aspiring reformist to be named in the same report as Russian oligarchs, Middle Eastern dictators, and bosses of the Naples mafia.

At the time of the 2019 presidential election, Volodymyr Zelensky struck a sharp contrast to the scandal-laden incumbent Petro Poroshenko. His relative youth (41 years old against Peroshenko’s 53), along with his background as a comedian parodying modern Ukrainian politics, helped propel him to the presidency of a country defined by constant cycles of proposed reforms and disappointing realities. However, a currently disappointing presidency seemingly makes it clear that youth in governance isn’t much of a cure-all for a country like Ukraine with a long history of corruption, financial graft, and backstage political machinations. However, there remains some hope for improvement: last year, Ukraine’s parliament passed an important anti-graft bill meant to halt fraudulent theft of international aid money, and Zelensky has recently proposed legislation aimed at weakening the political and economic influence of the country’s oligarchs—though whether these proposals materialize into law remains to be seen.[x][xi]

Zelensky’s predecessor, Petro Poroshenko, went through much the same story as his successor. After being elected on a “tough on corruption” platform, Poroshenko passed some moderate reforms but was ultimately voted out of office after the public grew disillusioned with a lack of true change. The subsequent disappointments of Zelensky’s stalled anti-corruption efforts have thus driven home the idea that youth and reform are not synonymous in Ukraine’s political leaders, who preside over a country where the “reformist” label often boils down to taking a tough stance on corruption—and little else.

Ethiopia

Abiy Ahmed’s ascension to president of Ethiopia in 2018 marked a turning point in a nation troubled by conflict, hunger, and poverty.[xii] Ahmed promised a refreshing new approach to governance and pledged to unite the country’s political, ethnic, and religious factions while increasing political representation and inclusion. In the early days of his presidency, these promises seemed to hold as Ethiopians and the international community alike embraced Ahmed’s progressive and liberalizing reforms—personified in Ahmed’s young, fresh, and perpetually smiling image.[xiii] Tens of thousands of political prisoners jailed under the previous regime were released, a national state of emergency which curtailed civil liberties and expanded military powers was lifted two months ahead of schedule, and the ruling party began talks with the opposition to amend a longstanding anti-terrorism law which critics have attacked as draconian and far in excess of the government’s rightful authority.[xiv][xv][xvi]

Abiy Ahmed’s greatest achievement came in 2019 when his efforts in resolving longstanding tensions between Ethiopia and Eritrea bore fruit. The two countries previously fought a border war in 1998-2000 and had been embroiled in constant tension and occasional conflict ever since. International analysts and domestic observers seriously doubted that either side would come to the table and finally end the war. Yet a final agreement to resolve the remaining tensions and the longstanding conflict was signed in 2018 under Ahmed’s leadership and diplomatic efforts, an astounding achievement and a stunning early victory for the yet-untested leader.[xvii]The international community responded with gusto to Ahmed’s success, and the young leader won the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize "for his efforts to achieve peace and international cooperation, and in particular for his decisive initiative to resolve the border conflict with neighbouring Eritrea.”[xviii]

Since presiding over the Eritrean peace, however, Abiy Ahmed’s leadership has been marred by an alarming backslide into burgeoning authoritarianism, repression of civil liberties, and a violent campaign against ethnic minorities. Ahmed’s fall from grace has centered around his military campaign against Tigray, one of the ten major regions of Ethiopia. Tigray is governed primarily by the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which lost considerable power, influence, and status after several of its leaders were removed from their posts due to charges of corruption in the wake of the new prime minister’s overhauls.[xix] Furthermore, the TPLF, outraged by Ahmed’s political reforms which sidelined regional governments in favor of a centralized approach, held its own local elections in 2020 in open defiance of the Ethiopian government’s earlier postponement of the ballot due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[xx] Finally, after months of escalating tensions and tit-for-tat denunciations, the increasingly polarized relations between Tigrayan regional leaders and the Ethiopian government under Abiy Ahmed finally came to a head. The situation erupted into violence in early November last year, when Ethiopian armed forces responded to a series of attacks against army bases (allegedly committed by Tigrayan soldiers) with a full-scale military operation into the Tigray region.[xxi]

Since the fighting began, both the Ethiopian government and Tigrayan forces have been accused of serious human rights violations, including mass killings and rape, extra-judicial killings, recruitment of child soldiers, arbitrary detention and torture of civilians, and widespread looting of villages already experiencing heavy fighting.[xxii] Abiy Ahmed’s moves to restrict access to power, Internet, and telecommunications systems throughout the Tigray region have severely reduced living standards for hundreds of thousands of people.[xxiii] The Ethiopian government’s recent declaration of a nationwide state of emergency (imposed in response to significant territorial gains by Tigray rebels over the previous few weeks) has also significantly curtailed civil liberties and freedoms for Ethiopian civilians, journalists, and government officials alike through curfews, communications blackouts, roadblocks, and military control over civilian population areas.[xxiv]

Conclusion

Abiy Ahmed’s actions in the Tigray conflict have burned much of his international reputation for progressive, conciliatory, and liberalizing policies due to his repressive campaign against the Tigray rebels. Even as the military campaign in Tigray rages, however, Ahmed’s domestic approval and political power have both skyrocketed to new heights. Ahmed’s Prosperity Party was recently re-elected with a huge parliamentary majority, winning 410 out of 436 legislative seats in the July elections, and his approval rating among Ethiopians recently reached 77%.[xxv] The veracity of Ahmed’s domestic approval rating and electoral success is incredibly dubious—according to the head of the national elections board, Birtukan Midekssa, government officials “were unable to hold elections in four of Ethiopia's 10 regions [and in] two of the regions that did vote, opposition observers were reportedly chased away from many polling stations.”[xxvi] Yet, barring a seismic shift in his public approval ratings or a drastic increase in sanctions against the Ethiopian government, Abiy Ahmed’s hold on power (in the parts of Ethiopia still under his control) seems secure.

Abiy Ahmed’s reversion to authoritarian violence and repression of civil liberties has now almost completely eclipsed his initial promise to be the young, dynamic face of reformist leadership in Ethiopia and in the broader region of East Africa. This reversal perhaps proves that, in Ethiopia, seemingly new approaches to governance under young, energetic leaders aren’t always enough to overcome age-old ethnic, political, and geographic conflicts that undermine any chances at real, lasting reform. Ukraine faces a similar challenge: decades of corruption, dysfunction, and oligarchical control of economic and political institutions have blunted any moves toward real reform—as shown by Volodymyr Zelensky’s disappointing time in office thus far. Perhaps, then, the world is better off placing its faith in time-tested leaders with proven records of comprehensive reform and liberal governance rather than newcomers promising entirely new approaches to power.

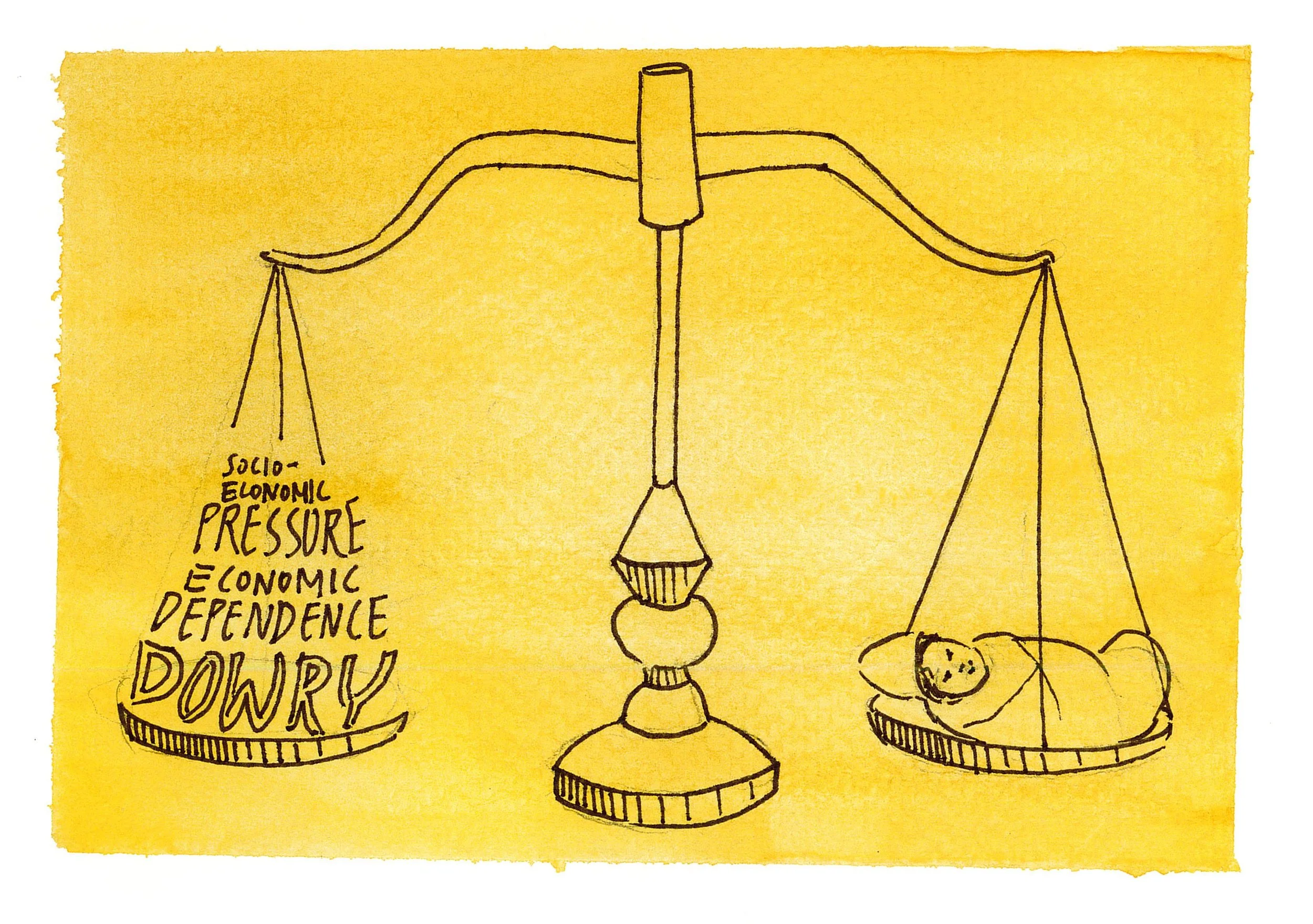

Illustration by Esther Wang

[i] Amnesty International USA. “Belarus.” Accessed November 14, 2021. https://www.amnestyusa.org/countries/belarus/.

[ii] “Signed by Volodymyr Zelenskyy: Which Reforms Did the President Support | VoxUkraine.” Accessed November 14, 2021. https://voxukraine.org/en/signed-by-volodymyr-zelenskyy-which-reforms-did-the-president-support.

[iii] ConstitutionNet. “A Weaker Ukrainian Parliament and de Facto Presidential System? Zelensky’s Constitutional Reform Initiatives.” Accessed November 14, 2021. https://constitutionnet.org/news/weaker-ukrainian-parliament-and-de-facto-presidential-system-zelenskys-constitutional-reform.

[iv] ConstitutionNet. “A Weaker Ukrainian Parliament and de Facto Presidential System? Zelensky’s Constitutional Reform Initiatives.” Accessed November 14, 2021. https://constitutionnet.org/news/weaker-ukrainian-parliament-and-de-facto-presidential-system-zelenskys-constitutional-reform.

[v] “Zelensky’s Presidency at the Two-Year Mark | Wilson Center.” Accessed November 14, 2021. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/zelenskys-presidency-two-year-mark.

[vi] Pifer, Steven. “Ukraine’s Zelenskiy Ran on a Reform Platform — Is He Delivering?” Brookings (blog), July 22, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/07/22/ukraines-zelenskiy-ran-on-a-reform-platform-is-he-delivering/.

[vii] Pifer, Steven. “Ukraine’s Zelenskiy Ran on a Reform Platform — Is He Delivering?” Brookings (blog), July 22, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/07/22/ukraines-zelenskiy-ran-on-a-reform-platform-is-he-delivering/.

[viii] Pifer, Steven. “Ukraine’s Zelenskiy Ran on a Reform Platform — Is He Delivering?” Brookings (blog), July 22, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/07/22/ukraines-zelenskiy-ran-on-a-reform-platform-is-he-delivering/.

[ix] “Pandora Papers: Ukraine Leader Seeks to Justify Offshore Accounts.” Accessed November 14, 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/10/4/pandora-papers-ukraine-leader-seeks-to-justify-offshore-accounts.

[x] Kramer, Andrew E. “Ukraine Passes a Critical Anticorruption Bill.” The New York Times, May 13, 2020, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/13/world/europe/ukraine-zelensky-corruption-kolomoisky.html.

[xi] Reuters. “Ukraine’s Leader Moves to Strip Oligarchs of Power with New Bill,” June 3, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ukraines-leader-asks-lawmakers-adopt-anti-oligarch-law-2021-06-02/.

[xii] “Ethiopia Swears in First PM from Ethnic Oromo Community.” Accessed November 14, 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/4/2/abiy-ahmed-sworn-in-as-ethiopias-prime-minister.

[xiii] “Ethiopia’s Abiy Ahmed: The Nobel Prize Winner Who Went to War.” BBC News, October 11, 2021, sec. Africa. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-43567007.

[xiv] “Ethiopia Offers Amnesty to Recently Freed Political Prisoners.” Reuters, July 20, 2018, sec. Emerging Markets. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ethiopia-prisoners-idUSKBN1KA1U0.

[xv] “Ethiopia Offers Amnesty to Recently Freed Political Prisoners.” Reuters, July 20, 2018, sec. Emerging Markets. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ethiopia-prisoners-idUSKBN1KA1U0.

[xvi] “Ethiopian Government and Opposition Start Talks on Amending Anti-Terrorism Law.” Reuters, May 30, 2018, sec. World News. https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-ethiopia-politics-idUKKCN1IV1RL.

[xvii] BBC News. “Ethiopia and Eritrea Peace Agreement.” Accessed November 14, 2021. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/topics/cen5x5l99w1t/ethiopia-and-eritrea-peace-agreement.

[xviii] NobelPrize.org. “The Nobel Peace Prize 2019.” Accessed November 14, 2021. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/2019/summary/.

[xix] “Ethiopia’s Tigray War: The Short, Medium and Long Story.” BBC News, June 29, 2021, sec. Africa. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-54964378.

[xx] “Ethiopia’s Tigray War: The Short, Medium and Long Story.” BBC News, June 29, 2021, sec. Africa. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-54964378.

[xxi] “Ethiopia’s Tigray War: The Short, Medium and Long Story.” BBC News, June 29, 2021, sec. Africa. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-54964378.

[xxii] UN News. “Multiple Reports of Alleged Human Rights Violations in Tigray,” September 13, 2021. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/09/1099812.

[xxiii] UN News. “Multiple Reports of Alleged Human Rights Violations in Tigray,” September 13, 2021. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/09/1099812.

[xxiv] “Ethiopia Declares State of Emergency in Opposition-Ruled Tigray.” Accessed November 14, 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/11/4/ethiopia-declares-state-of-emergency-in-opposition-tigray-region.

[xxv] Inc, Gallup. “Ethiopians Confident in Elections, Leadership.” Gallup.com, June 18, 2021. https://news.gallup.com/poll/351389/ethiopians-confident-elections-leadership.aspx.

[xxvi] “Ethiopians Vote as Opposition Alleges Some Irregularities.” Accessed November 14, 2021. https://www.yahoo.com/now/ethiopians-vote-government-bills-first-221356957.html.