Vulnerable Victims: How Disasters Impact Children

Vulnerable Victims:

How Disasters Impact Children

By Beatriz Slade

Disasters such as the 2005 Pakistan Earthquake, the 2014 West African Ebola epidemic, and the 2011 Japan Earthquake and Tsunami all take a unique toll on children through school closure, psychological trauma, and massive displacement. These impacts exacerbate children’s vulnerabilities in various areas including education, mental health, and housing. Natural disasters’ unpredictability and catastrophic effects generate a host of inequalities and obstacles that burden children for life.

Disasters’ Impact on Youth Education

Regardless of the length of school closures, disasters force students out of the classroom, which can lead to academic issues that exacerbate inequalities and have long-term implications on employment. In 2005, an earthquake ravaged Northern Pakistan and Kashmir, leaving between 73,000 and 86,000 people dead and devastating existing infrastructure.[i] 170,000 schools were destroyed and children were out of school for 14 days.[ii] These two weeks without classes significantly impacted the test scores and knowledge of affected children, whose academic progress fell approximately 1.5 to 2 years behind unaffected peers.[iii]

Other destructive disasters such as the West Africa Ebola crisis also intensified inequalities in academic performance through school closures. As a result of the Ebola crisis, 10,000 schools in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea were shut down for between six and eight months, and students lost between 486 and 780 learning hours.[iv] Attempts to continue academic engagement were further challenged by pre-existing issues like inadequate radio signals, different language dialects, and difficult to decipher accents.[v] As the crisis subsided, it became clear that academic achievement had fallen behind. After the crisis, a NBIH study concluded that youth experienced high dropout levels, with 17,400 more dropouts than average attributed to the impacts of Ebola.[vi]

In addition to the immediate consequences of the shut-downs, school closures stifle academic growth and cause life-long adverse economic effects. While the true economic cost of the earthquake and Ebola have yet to be measured, the effects of the Argentina Teacher Strikes serves as a worthy comparison. Though not a consequence of a natural disaster, the Argentina Teacher Strikes exemplify the negative influence of school closures, with these strikes leading to a lack of educational attainment which, in turn, led to a decrease in employment for affected children. A study concluded that male students affected by the strikes had an average earnings loss of 3.2% and experienced significant occupational downgrades, while female students had an average earnings loss of 1.9% and experienced an increase in home production.[vii] This highlights the influence of education on economic inequality, especially in times of disruption. This same prediction was made for children affected by the 2005 Pakistan Earthquake, with low-income children who lost two weeks of school predicted to have a 15% decrease in future earnings.[viii] Similarly in West Africa, where attaining a high school diploma is instrumental in increasing wages, higher drop out rates for affected students undoubtedly exacerbated the economic inequalities within the future workforce.[ix] The results of the Argentina Teacher Strikes support the prediction that the Pakistan and West Africa disasters, which both caused school closures, will have significant impacts on affected children’s future earnings, occupation, and women’s likelihood to join the workforce, which will be worse for students without access to academic engagement like government programs and education-oriented families.

Disasters’ Impact on Youth Mental Health

Disasters disrupt childrens’ daily life, generating mental health issues and feelings of isolation and stigmatization that affect their behavior. The 2005 Pakistan Earthquake occurred on a school day, with many children witnessing their classrooms collapse and classmates sustain life-threatening injuries. They were left in a state of uncertainty, not knowing what was happening and whether their friends or families were alive. Since children are more psychologically vulnerable than adults, this traumatic experience caused a host of mental health issues post-earthquake.[x] The feelings of loss of control experienced by Pakistani youth manifested as post-traumatic-stress-disorder, depression, anxiety, and conduct disorders.[xi] 18 months after the earthquake, 64.8% of earthquake-affected Pakistani children experienced symptoms of PTSD and 34.6% had emotional and behavior difficulties.[xii] One expression of the lingering psychological impacts was students’ inability to concentrate in the classroom. Many students exhibited antisocial behavior, poor conduct, difficulty staying awake, feelings of isolation, and reluctance to plan for their future, highlighting not only the damaging consequences of disasters on behavior, but also on educational attainment.[xiii]

Similarly, the West Africa Ebola crisis severely impacted children’s mental health, specifically Ebola survivors, through the stress caused by cultural beliefs surrounding Ebola. More than 3,600 children were infected with Ebola and at least 16,000 children lost a parent due to the outbreak.[xiv] Children who contracted Ebola were isolated, and many had at least one parent in quarantine. Unsurprisingly, the Ebola crisis generated feelings of isolation, abandonment, and shame for children.[xv] Cultural beliefs due to misinformation about the disease, low institutional trust, and a history of shaming those who contract an infectious disease all fed into Ebola stigmatization in West Africa.[xvi] In order to avoid shunning, many families refused to test their children for Ebola and hid patients in their homes.[xvii] As a result of this stigmatization, Ebola survivors felt high levels of abandonment even after reintegrating into regular life.[xviii] Many Ebola survivors, including children, had their clothes burned, were abandoned by their families, and were told to not return home.[xix] Research found that Ebola survivors faced psychological distress including anger, grief, guilt, flashbacks, worthlessness, and suicidal tendencies.[xx] Children who had contracted the infection or were suspected of being exposed also experienced social isolation and stigmatization among peers.[xxi] The impact of these experiences is highlighted by the dramatic increase in the number of children who received psychological support. For instance, in Liberia, from February 2015 to December 2015, the surge in children who received psychological support was 3,707 to 122,213.[xxii] The West Africa Ebola crisis severely impacted children’s mental health, specifically those who survived the disease, through the stress generated by cultural beliefs surrounding Ebola.

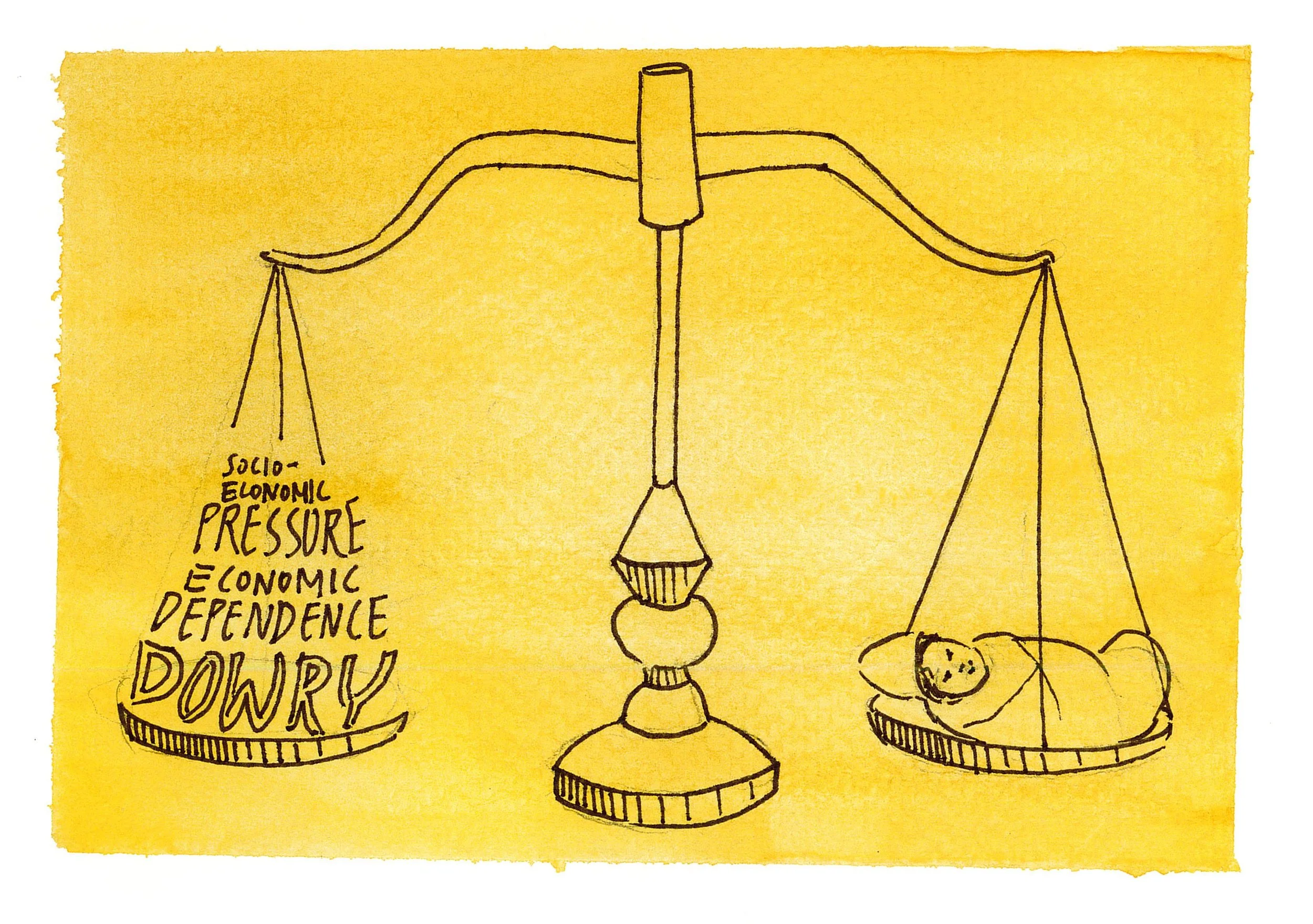

The outbreak also led to a spike in teen pregnancies and female exploitation, further exacerbating mental health issues. Without the safety of open schools, young girls spent more time at home, leaving them more vulnerable to domestic violence, rape, and sexual exploitation.[xxiii] In Sierra Leone, teen pregnancy increased by 65% compared to before the Ebola crisis. Additionally, manys girls turned to prositution as they lost family members and therefore income for their households, and instances of rape and assualt also increased.[xxiv] In Liberia in 2015, 401 out of 450 rape cases were towards girls under the age of 18.[xxv] After the outbreak, the NGO Save the Children interviewed 617 girls in Sierra Leone. 10 percent of the interviewed girls –many of whom lost at least one parent to Ebola – turned to sex work as a way to provide for themselves. Furthermore, many indicated that all most all the girls they knew who were quarantined due to the virus were victims of sexual assault.[xxvi] The rise in teenage pregnancy and the mental trauma of experiencing sexual exploitation during the outbreak generated and exacerbated psychological issues for young girls.

Disasters’ Impact on Youth Displacement

Displacement triggered by disasters severely disrupts children’s housing and access to basic necessities, which exacerbates mental health and education issues. The 2011 Japan earthquake and tsunami, for example, generated massive displacement as it ravaged almost all of Japan’s infrastructure, damaging 4,00 schools, and displacing 10,000 children.[xxvii] Since children have an increased risk for tumour induction and there was a radiation leak from the Fukushima nuclear power plant, families with children were more likely to be voluntary evacuees and were more likely to switch housing.[xxviii] 36,000 families with children fled the Fuskhuma prefecture, with 10,000 still not having returned home five years later. [xxix] One shelter in Sendai’s composition was 25% children. [xxx] Similarly, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa instigated a wave of migration of people away from virus hotspots. Minimal to no information on the transmission of Ebola was available to Africans, prompting many to flee their homes as a preventative measure. Quarantines were haphazardly and inconsistently imposed in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, leading to confusion, food insecurity, violence, and attempts to escape quarantines. Both the West Africa Ebola outbreak and the 2011 Japan Earthquake and Tsunami uprooted children’s lives through displacement.

The displacement caused by the West Africa Ebola outbreak and the 2011 Japan Earthquake and Tsunami had adverse impacts on children, especially regarding their mental health. Save the Child interviewed displaced children and reported trends of children being afraid to go home, missing their friends, and wanting to return to school.[xxxi] Investigations on the effects of internally displaced people indicate that children feel intense sadness about leaving behind their families and friends and that many displaced children are subject to sexual assault and violence. Additionally, the study mentions that children face psychological problems such as stress, difficulty concentrating, lack of interest in socialization and school, out of character aggression, and even the inability to continue to develop properly as consequences of being internally displaced.[xxxii] The mental health consequences and lack of consistency in youth’s lives when they are displaced are a huge barrier to their development.

Implications

While the young can never be fully protected from the impacts of disasters, intervention is crucial for mitigating severe consequences. It is essential that academic services, mental health support, and disaster-readiness strategies be available to children affected by disasters. Ultimately, the inequalities produced by disasters, including the 2005 Pakistan Earthquake, the 2014 West Africa Ebola crisis, and the 2011 Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, leave children vulnerable to unique academic, psychological, and housing challenges. Assistance in the areas of education, mental health, and displacement are imperative for giving vulnerable youth the support they need to bridge disaster-instigated inequalities.

Illustration by Esther Wang

[i]. “The Kashmir Earthquake of October 8, 2005: Impacts in Pakistan - Pa- kistan,” ReliefWeb, accessed November 1, 2021, https://reliefweb.int/report/ pakistan/kashmir-earthquake-october-8-2005-impacts-pakistan.

[ii]. “Kashmir Earthquake,” ReliefWeb.

[iii]. “New Study Reveals Long-Term Impact of Disaster-Related School Clo- sures,” University of Oxford, accessed November 17, 2021, https://www.ox.ac. uk/news/2020-05-29-new-study-reveals-long-term-impact-disaster-related- school-closures/.

[iv]. “Socio-Economic Impact of the Ebola Virus Disease in West Africa: UNDP in Africa,” UNDP, accessed November 1, 2021, https://www.africa.undp.org/ content/rba/en/home/library/reports/socio-economic-impact-of-the-ebola-vi- rus-disease-in-west-africa.html.

[v]. Shawn Powers and Kaliope Azzi-Huck, “The Impact of Ebola on Education in Sierra Leone,” World Bank Blogs, accessed October 26, 2021, https://blogs. worldbank.org/education/impact-ebola-education-sierra-leone.

[vi]. William C. Smith, “Consequences of School Closure on Access To Educa- tion: Lessons from the 2013–2016 Ebola Pandemic,” International Review of Education 67, no. 1-2 (2021): pp. 53-78, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-021- 09900-2.

[vii]. David Jaume and Alexander Willén, “The Long-Run Effects of Teacher Strikes: Evidence from Argentina,” Journal of Labor Economics 37, no. 4 (2019): pp. 1097-1139, https://doi.org/10.1086/703134.

[viii]. Chad Aldeman, “Aldeman: What a 2005 Earthquake in Pakistan Can Teach American Educators about Learning Loss after a Disaster,” Aldeman: What a 2005 Earthquake in Pakistan Can Teach American Educators About Learning Loss After a Disaster, July 28, 2020, https://www.the74million.org/article/ aldeman-what-a-2005-earthquake-in-pakistan-can-teach-american-educators- about-learning-loss-after-a-disaster/.

[xi] “Education and Income: How Learning Leads to Better Salaries,” The Learn- ing Agency, April 13, 2021, https://www.the-learning-agency.com/insights/ education-and-income-how-learning-leads-to-better-salaries/.

[x] Ebru Şalcıoğlu and Metin Başoğlu, “Psychological Effects of Earthquakes in Children: Prospects for Brief Behavioral Treatment,” World Journal of Pediat- rics 4, no. 3 (2008): pp. 165-172, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-008-0032-8. 11. Şalcıoğlu and Başoğlu, “Psychological Effects of Earthquakes.”

[xii] Muhammad Ayub et al., “Psychological Morbidity in Children 18 Months after Kashmir Earthquake of 2005,” Child Psychiatry & Human Development 43, no. 3 (December 2011): pp. 323-336, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-011- 0267-9.

[xiii] Gayla Margolin, Michelle C. Ramos, and Elyse L. Guran, “Earthquakes and Children: The Role of Psychologists with Families and Communities.,” Profes- sional Psychology: Research and Practice 41, no. 1 (2010): pp. 1-9, https://doi. org/10.1037/a0018103.

[xiv]. “Ebola Crisis: Facts, Faqs & How to Help,” Save the Children, accessed October 26, 2021, https://www.savethechildren.org/us/what-we-do/emergen- cy-response/ebola-crisis.

[xv]. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, “Children's Needs in an Ebola Vi- rus Disease Outbreak,” The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 3, no. 2 (2019): p. 55, https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-4642(18)30409-7.

[xvi]. Patrick Vinck et al., “Institutional Trust and Misinformation in the Re- sponse to the 2018–19 Ebola Outbreak in North Kivu, DR Congo: A Popula- tion-Based Survey,” The Lancet Infectious Diseases (Elsevier, March 27, 2019), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1473309919300635?via%- 3Dihub.

[xvii]. “Factors That Contributed to Undetected Spread,” World Health Orga- nization (World Health Organization), accessed November 1, 2021, https:// www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/one-year-into-the-ebola-epidemic/ factors-that-contributed-to-undetected-spread-of-the-ebola-virus-and-imped- ed-rapid-containment.

[xviii]. Luc Overholt et al., “Stigma and Ebola Survivorship in Liberia: Results from a Longitudinal Cohort Study,” PLOS ONE13, no. 11 (2018), https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206595.

[xix]. “Cultural Contexts of Ebola in Northern Uganda - Volume 9, Number 10-October 2003 - Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal - CDC,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), accessed October 26, 2021, https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/9/10/02-0493_ article.

[xx]. P. B. James et al., “Post‐Ebola Psychosocial Experiences and Coping Mech- anisms among Ebola Survivors: A Systematic Review,” Wiley Online Library (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, March 20, 2019), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/ doi/10.1111/tmi.13226.

[xxi]. Shawn Powers and Kaliope Azzi-Huck, “The Impact of Ebola on Educa- tion in Sierra Leone.”

[xxii]. Swace Digital, “Care and Protection of Children in the West African Ebola Virus Disease Epidemic: Lessons Learned for Future Public Health Emergen- cies,” Resource Centre, accessed November 1, 2021, https://resourcecentre. savethechildren.net/pdf/final-ebola-lessons-learned-dec-2016.pdf/.

[xxiii]. Cassie Werber, “How Ebola Led to More Teenage Pregnancy in West Africa,” Quartz (Quartz), accessed October 26, 2021, https://qz.com/afri- ca/543354/how-ebola-led-to-more-teenage-pregnancy-in-west-africa/.

[xxiv]. Weber, “Ebola.”

[xxv]. Monica Adhiambo Onyango et al., “Gender-Based Violence among Adolescent Girls and Young Women: A Neglected Consequence of the West African Ebola Outbreak,” Global Maternal and Child Health, 2019, pp. 121- 132, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97637-2_8.

[xxvi]. Seema Yasmin, “The Ebola Rape Epidemic No One's Talking ... - Foreign Policy,” accessed November 1, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/02/02/ the-ebola-rape-epidemic-west-africa-teenage-pregnancy/.

[xxvii]. “Save the Children: Japan Earthquake Tsunami Relief,” GlobalGiving, accessed November 1, 2021, https://www.globalgiving.org/projects/ save-the-children-japan-earthquake-tsunami-relief/.

[xxviii]. “Save the Children: Japan Earthquake Tsunami Relief,” GlobalGiving.

[xxix]. “Save the Children: Japan Earthquake Tsunami Relief,” GlobalGiving.

[xxx]. Justin McCurry, “Japan Earthquake: 100,000 Children Displaced, Says Charity,” The Guardian (Guardian News and Media, March 15, 2011), https:// www.theguardian.com/world/2011/mar/15/japan-earthquake-children-dis- placed-charity.

[xxxi]. Save the Children International, “Children in Earthquake and Tsunami-Hit Communities Face Growing Risk of Disease Outbreak and Water-Borne Illness, Warns Save the Children,” Save the Children International, October 3, 2018, https://www.savethechildren.net/news/children-earthquake-and-tsuna- mi-hit-communities-face-growing-risk-disease-outbreak-and-water.https:// reliefweb.int/report/japan/100000-children-displaced-japan-earthquake-and- tsunami-warns-save-children.

[xxxii]. “Internally Displaced Persons,” Children and Youth in Armed Conflict (2 Vols.), January 2013, pp. 693-784, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004260269_011.