A Bridge Too Far: Young Athletes in Brazil and Venezuela’s Beauty Pageant Contestants

A Bridge Too Far:

Young Athletes in Brazil and Venezuela’s Beauty Pageant Contestants

By Phillip Chao

In Brazil and Venezuela, two Latin American countries, sharp wealth gaps, stagnant economic growth, and chaotic politics marked by corruption and instability have grown in recent decades. The prospects of becoming a professional athlete or an international beauty queen and rising to fame now appear more alluring than ever to underprivileged boys and girls facing such adversities. Hoping to escape the poverty trap and secure a better future for themselves and their families, adolescents look up to Latino celebrities on televisions and news stories, hoping to replicate their “rag to riches” stories. Many admire footballers such as Ronaldo Luís Nazário de Lima, who played on the streets of favelas in Rio de Janeiro before being discovered by scouts, competed for European clubs such as FC Barcelona, Inter Milan, and Real Madrid, won the Ballon d’Or award in 1997, and was widely regarded as a Brazilian national hero. Others are inspired by the story of Irene Sáez, the former Venezuelan beauty queen who was crowned Miss Universe in 1981, forging a successful political career as Mayor of Chacao, and eventually challenging Hugo Chávez in the 1998 presidential election.

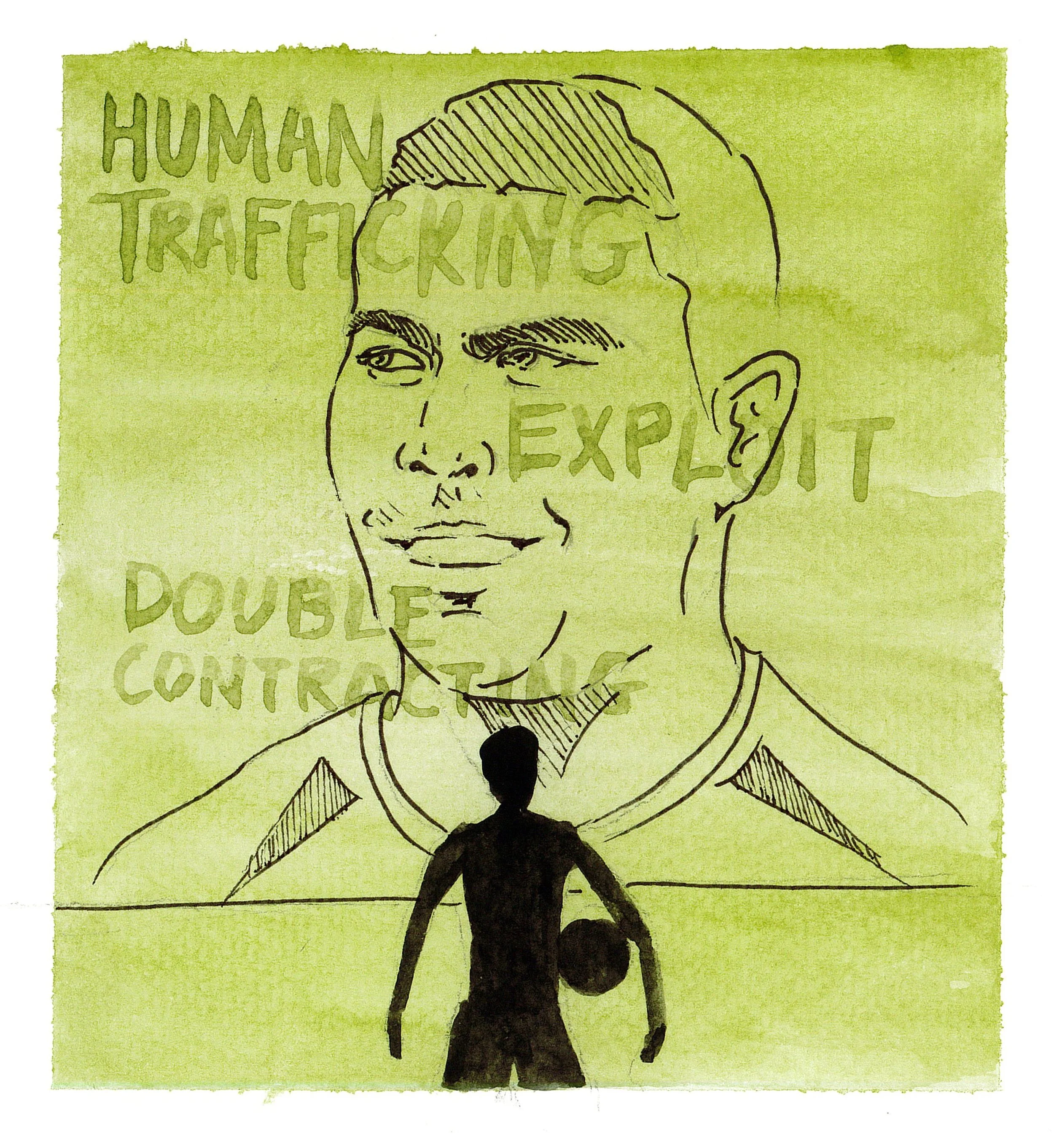

However, reality is almost always grimmer than what sports movies like Goal! and glamorous shows such as Miss Universe depict. From human trafficking rings targeting adolescent soccer players to sexual exploitation of young beauty contestants, disadvantaged boys and girls in Brazil and Venezuela who are seeking to fulfill their dreams and support their families have faced, and continue to face, intense commodification, institutionalized exploitation, and the risk of human trafficking as a result of corporate and political corruption.

“The Money Game”: Exploitation of Young Athletes and Human Trafficking Traps

In their search for better futures abroad, young athletes in Latin America face economic exploitation and are vulnerable to human trafficking rings due to information asymmetries, ineffective regulation, and the “profit-first” culture many clubs in Europe have adopted. For instance, young soccer players from Latin America, lured by the prospect of playing for a European team, often fall prey to human traffickers who pose as legitimate agents and promise them opportunities for “overseas tryouts.” In his book Human Rights in Youth Sport, author Paulo David notes that 24 Brazilian footballers, several of whom were minors, were detained and threatened with deportation in the Dutch territory of Aruba when authorities accused them of participating in a human trafficking scheme in the Netherlands.[i] David also raises the example of a criminal syndicate operating in Portugal and trafficking teenage Brazilian players to continental Europe.[ii] Due to Brazil and Portugal’s close diplomatic ties and shared language and culture, many Brazilian players chose to start their European careers in Portugal. Primeira Liga, the top league in the nation, had 373 Brazil-born players at one point, representing 55.1% of the foreign players in the association.[iii] Indeed, the close ties and relative ease of travel between the two countries may have indirectly aided “football traffickers” searching for vulnerable targets.

On the other hand, while many cases of “football trafficking” are conducted by international criminal syndicates, some are performed under the disguise of legitimate sports agencies. Despite regulations set up by the International Federation of Association Football (FIFA) and European governments, some international sports agents continue to exploit foreign players by opening up unlicensed academies in underdeveloped countries.[iv] These academies are often “roadside operations” that “lack proper facilities and equipment,” and lure aspiring players and their families to pay “excessive upfront fees,” often forcing them into exploitative agreements.[v] Other agents use social media to cajole young athletes into their hoaxes, disseminating untruthful recruitment ads and directly engaging potential targets on Facebook messenger.[vi] In the end, the unobstructed presence of these schemes pinpoints the ineffectiveness of government regulations in Europe. Despite the passage of the United Kingdom’s Modern Slavery Act (MSA) in 2015, which outlaws different forms of compulsory labor by corporates and applies to all football clubs and sports agencies in the UK, an estimated 2,120 children were still being trafficked to Britain to play football two years later, in 2017.[vii] The root cause of this issue lies in a deep-seated global inequality of resources and capital that prompts organisations, including sports clubs to “make profits by exploiting [the] cheaper human resources,” which are typically available in underdeveloped nations in the Global South.[viii]

The volatility of international politics often further complicates up-and-coming athletes’ searches for opportunities abroad, as it has for Cuban baseball players. The uncertainties posed by US sanctions and policy swings between different administrations have made many more vulnerable to organized traffickers. For instance, President Obama’s signals of relaxation on Cuba sanctions was immediately followed by President Trump’s more hard-line stance, forcing young Cubans to move to a transit country and seek potential contracts from there.[ix] Even for the lucky youngsters that have made it to lower division teams abroad or joined elite youth academies, success remains a “dream too far”.[x]

For aspiring Latin American soccer players, the situation is not much better. Indeed, out of the tens of thousands of players in the UK’s youth football development programs, less than 1% “go on to make a living out of the game,” let alone to play on Premier League grounds.[xi] Some European clubs deliberately underpay foreign youngsters, take away their passports and means of communication with their families and friends, and, if their contracts are not renewed, eventually leave them stranded overseas.[xii] In Belgium, “double-contracting,” for foreign players, many of whom come from Latin America, has become a common practice. Unlicensed “sports agents” take financial advantage of young players by making two contracts; a legitimate, rule-abiding version is submitted to the Football Federation, while the youth players receive one that often entails harsh conditions and underpayment.[xiii] Although FIFA has repeatedly condemned “football trafficking” and punished offending clubs, including prominent names like FC Barcelona and Atlético Madrid, for underage recruitment overseas, the situation did not seem to ameliorate.[xiv] Despite the international sports community’s best efforts to raise awareness on the issue and legislate new protection measures, the deep-rooted cause of the problem is in fact the generational socio-economic inequality in the Global South, declining job market prospects, and lack of social support that leave young boys and girls no choice but to go after the remotest possibilities.

“Maduro’s Girls”: Venezuela’s Beauty Industry and its Political Ties

Almost in parallel to the youth athletes aspiring to play for European and North American clubs, many young girls in Latin America, namely Venezuela and Colombia, dream of escaping the poverty cycle by participating in beauty pageants. In Venezuela, beauty pageant shows remain an integral part of national celebration: the image of young contestants in high heels and bikini skirts competing on stage in some way covers up the nation’s pressing socio-economic problems, including its income inequality, food and essential supply shortages, and political corruption.[xv] To date, Venezuelan nationals have lifted 23 crown titles of Miss World, Miss Universe, Miss International, and Miss Earth–more than any other country in the world.[xvi] This all took place in a nation deeply troubled by hyperinflation and high unemployment. Earlier this year, the monthly inflation rate in Venezuela skyrocketed to 28.5%, while the minimum wage still hovered around $2.40.[xvii] Despite this, many families willingly invest their life savings to send their daughters, sometimes as young as four, to one of the nation’s “beauty pageant factories” where they undergo rigorous training to adhere to the idealized mannerism and beauty standards.[xviii] Expensive plastic surgery, cosmetics, and beauty products further drain these families of their meagre savings.[xix] The “craze to win” exacerbates the commodification of young women, who essentially become replaceable human parts of a national money-making machine valued solely by the numerical scores given by male judges.

What adds onto the burdens and harm placed on beauty pageant contestants is the power imbalance between the young girls, who generally come from lower income families, and the beauty industry tycoons. The entanglement between the ruling government and its booming “beauty industries” highlights the underlying issues of institutional abuses at the hands of industry magnates and government officials that plague the industry. Many of these people have jointly benefited from shows filled with exploitation and over-sexualization. For instance, Osmel Sousa, the “Beauty Czar” of Venezuela and long-term president of the Venezuelan Committee of Beauty, allegedly pimped out young contestants to politicians and businessmen as escorts or concubines.[xx] One of the politicians linked to the scandal, Maikel Moreno, was a convicted murderer and a leading figure in Maduro’s repressive regime, serving as the President of the Venezuelan Supreme Tribunal of Justice and notorious for his persecution of the regime’s political opposition.[xxi] Other officials would manipulate beauty pageant winners into acting as their money-laundering agents abroad: for instance, a former Venezuelan beauty queen was arrested by Spanish police in 2018, accused of depositing money linked to a Venezuelan state-owned oil company.[xxii] Despite the allegations and subsequent international backlash, Sousa remained influential in Latin America’s beauty pageant circle, claiming to be a friend of Donald Trump while currently serving as the National Director of Miss Universe Argentine and Miss Universe Uruguay. Miss Venezuela, a former symbol of national pride, now exists as a tool of Nicolás Maduro’s increasingly authoritarian regime, distracting its domestic and international audiences from the nation’s mounting crises, while its contestants were subjected to physical harm, mental torment, commodification, and institutionalized abuses.

Socio-economic Inequality: Drivers of Exploitation

While political entanglement in Venezuela’s beauty industries directly led to institutionalized abuse, administrative negligence, on national and international levels, was also a driving force behind the exploitations of young Brazilian soccer players. Getting to the root of the problem–corporate and individual greed–is a crucial step to combating it. However, a more comprehensive social safety net may provide these teenagers with a quality education and alleviate the burden of supporting their families. Tightening regulations, such as increasing the penalties and fines on offenders in replacement of current legislationsand cracking down on human trafficking rings will help breed a cleaner, safer environment for young players. For instance, revising UK’s MSA regulations, which only require clubs and agents to “pledge” that they will not engage in human trafficking and exploitation, can be a start to ensuring that there is adequate government enforcement to mitigat these issues. Finally, a balanced, diversified economy can guarantee safer job opportunities close to home; for the great majority of youth players that fail to make professional team rosters, they can still be employed and support their families.

The Future of Uncertainty Ahead

Whether it is the teenage boys playing a makeshift soccer match on the streets of Benton Ribeiro, or school-age girls posing in oversexualized constumes and practicing runway walks inside a small, cramped room in the suburbs of Caracas, adolescents in Latin America countries like Brazil and Venezuela, aspiring to uplift their families out of poverty, inevitably find themselves entrapped and exploited by human traffickers, money-driven corporations, and politically connected industry moguls. As their dreams evaporate, disadvantaged youth in Brazil and Venezuela now face a future marked by uncertainty and insecurity. These issues can only be addressed by institutional reform, stricter regulations, and a comprehensive social safety net. With the help of international institutions like FIFA or UNICEF, International Non-Governmental Organizations (INGOs), and Transnational Advocacy Networks (TANs), governments and local authorities have the responsibility as well as the capability to secure the adolescents a safe, foreseeable tomorrow.

Illustration by Esther Wang

[i]. Brendan Howe

[i]. James Esson and Eleanor Drywood, “Challenging Popular Representations of Child Trafficking in Football,” figshare (Loughborough University, August 11, 2019), https://repository.lboro.ac.uk/articles/journal_contribution/Challenging_popular_representations_of_child_trafficking_in_football/9484400.

[ii]. Esson, Drywood, “Challenging Popular.”

[iii]. Carlos Nolasco, “Player Migration in Portuguese Football: a Game of Exits and Entrances ,” Soccer & Society 20, no. 6 (January 10, 2018): pp. 795-809, https://doi.org/https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14660970.2017.1419470.

[iv]. University of Nottingham Rights Lab, “The Problem of Sports Trafficking ... - Nottingham.ac.uk” (University of Nottingham, August 2021), https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/beacons-of-excellence/rights-lab/resources/reports-and-briefings/2021/august/the-problem-of-sports-trafficking.pdf.

[v]. University of Nottingham Rights Lab, “The Problem.”

[vi]. University of Nottingham Rights Lab, “The Problem.”

[vii]. Kieran Guilbert, “Premier League Concerned by Children Trafficked to UK by Football 'Fraudsters',” Reuters (Thomson Reuters, April 23, 2018), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-britain-slavery-soccer/premier-league-concerned-by-children-trafficked-to-uk-by-football-fraudsters-idUSKBN1HU1UJ.

[viii]. Ini-Obang Nkang, “Modern Slavery: The Trafficking of African Minors to European Football Leagues,” APPG (All-Party Parliamentary Group on Sport, Human Rights and Modern Slavery, July 2019), https://www.appgshr.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Ini-Obong-Nkang_APPG-submission-on-Mordern-Slavery_Final.pdf.

[ix]. University of Nottingham Rights Lab, “The Problem.”

[x]. Rob Dawson, “Academy Players Reveal Mental Health Impact of Being Released: 'My Lowest Point Was Not Knowing If I Would Play Again',” ESPN (ESPN Internet Ventures, September 7, 2021), https://www.espn.com/soccer/manchester-united-u21/story/4451732/academy-players-reveal-mental-health-impact-of-being-released-my-lowest-point-was-not-knowing-if-i-would-play-again.

[xi]. Rob Dawson, “Academy Players.”

[xii]. University of Nottingham Rights Lab, “The Problem.”

[xiii]. Esson, Drywood, “Challenging Popular.”

[xiv]. Esson, Drywood, “Challenging Popular.”

[xv]. Associated Press, “In Beleaguered Venezuela, Young Women Use Beauty Pageants to Escape Poverty,” NBCNews.com (NBCUniversal News Group, July 6, 2018), https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/beleaguered-venezuela-young-women-use-beauty-pageants-escape-poverty-n889361.

[xvi]. Katharina Buchholz, “Infographic: The Countries with the Most Beauty Pageant Crowns,” Statista Infographics (Statista, May 17, 2021), https://www.statista.com/chart/23718/countries-with-most-big-four-beauty-pageant-titles/.

[xvii]. Reuters, “Venezuela Monthly Inflation Hits 28.5% in May, Central Bank Says,” Reuters (Thomson Reuters, June 16, 2021), https://www.reuters.com/article/venezuela-inflation/venezuela-monthly-inflation-hits-28-5-in-may-central-bank-says-idUSL2N2NY2I5#:~:text=Venezuela%20monthly%20inflation%20hits%2028.5%25%20in%20May%2C%20central%20bank%20says,-By%20Reuters%20Staff&text=CARACAS%2C%20June%2016%20(Reuters),nation%20struggles%20to%20contain%20inflation.

[xviii]. Sarah Grainger, “Inside a Venezuelan School for Child Beauty Queens,” BBC News (BBC, September 2, 2012), https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-19373488.

[xix]. Hannah Dreier, “Plastic Surgery-Obsessed Venezuela Hit by Shortage of Breast Implants,” CTVNews (CTV News, September 15, 2014), https://www.ctvnews.ca/lifestyle/plastic-surgery-obsessed-venezuela-hit-by-shortage-of-breast-implants-1.2006950#:~:text=Venezuela%20is%20thought%20to%20have,Society%20of%20Aesthetic%20Plastic%20Surgery.

[xx]. Tal Abbady, “Pimping out Miss Venezuela,” The New York Times (The New York Times, May 19, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/19/opinion/sunday/miss-venezuela-corruption.html.

[xxi]. Tal Abbady, “Pimping out Miss Venezuela.”

[xxii]. Tal Abbady, “Pimping out Miss Venezuela.”