The Young Pioneers of Autocracy: Investigating the Role of Children in Russian Propaganda

The Young Pioneers of Autocracy:

Investigating the Role of Children in Russian Propaganda

By Evan Sierra

In July of 2014, several months after the Russian annexation of Crimea and the start of the war in Ukraine’s Donbas region, the Russian state media platform Channel 1 News broadcast a particularly gruesome news story. The report featured an interview with a local woman from the Eastern Ukrainian city of Slovyansk, in which she recounted horrific war crimes committed by pro-Ukrainian forces. As she recalled, Ukrainian soldiers publicly crucified a young boy in retaliation for his father’s support of pro-Russian separatism. Despite her harrowing account of the incident, the story had no factual basis, and soon came under intense scrutiny. Investigators from the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta found no one in Slovyansk to corroborate the claim.[i] In a rare, partial admission of journalistic malfeasance, Channel 1 News later reported that the story may have been a “sick fantasy.”[ii]

As extraordinary as the case of the “crucified boy” may appear, it is only one instance of a broader trend in Russian propaganda: depicting threats to Russian children. While this strategy is not unique to Russia, it is especially prominent in its propaganda due to historical and cultural legacies. Russia employs this strategy not only in Ukraine, but in the Baltic States, Western Europe, and abroad. Understanding how children are used in Russian propaganda may provide broader insight on the Kremlin’s goals and its overall strategy for achieving them. By using the motif of victimized children, the Kremlin seeks to manufacture humanitarian crises, consolidate its domestic control, and weaken Western unity.

The Significance of the Child Motif in Russia

The use of children in Russian propaganda is deeply rooted in Russian cultural traditions. In the medieval era, Orthodox Christian iconography was the preeminent method of conveying theological messages to the largely illiterate peasantry.[iii] The image of the “Theotokos” was especially prominent. Much like Madonna iconography of the Catholic tradition, the Theotokos depicts Christ not as a man, but as a vulnerable infant in the arms of the Virgin Mary. The most famous of all Theotokos icons, Our Lady of Vladimir, “was one of the most popular and revered symbols of national consciousness in old Russia.”[iv] Russia’s tradition of iconography contributed to a strong association between Christian virtue and vulnerability that would later manifest itself in propaganda.

The cultural legacy of Theotokos iconography was reinforced by Russia’s experience of the Second World War. To dehumanize the German invaders, Soviet propaganda emphasized Nazi crimes against Soviet children in posters, film, and literature. In one widely distributed poster labeled “Warriors of the Red Army, Save Us,” a peasant woman donning a shawl clutches a young boy in her arms as they face the end of a bayonet.[v] The visual similarity between the poster and the Theotokos image would have been unmistakable to contemporary Russians, suggesting a deliberate effort by the Soviet government to capitalize off past symbols of national identity. Even when divorced from their religious origin, images of suffering children were especially poignant to Soviet citizens of the time. During the war, the total population of Soviet children decreased by a staggering 14 million—ten times as many as the rest of Europe combined.[vi] The war’s devastating costs on children gave them a unique status in post-war Soviet society. The Soviet government launched a campaign to promote a “happy childhood,” and foreign observers noted that “children had a privileged place in the Soviet way of life.”[vii] As a result of these historical legacies, children continue to occupy a prominent role in Russian propaganda today.

Hawkishness on Humanitarian Grounds

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, humanitarian concerns have played a key role in the Kremlin’s efforts to justify its foreign policy. Many of these concerns stem from enduring issues surrounding the Russian diaspora. In both the Imperial and Soviet era, large numbers of ethnic Russians migrated among imperial territories and national republics. But when the USSR abruptly fragmented into 15 independent states in 1991, 25 million ethnic Russians found themselves outside the borders of their homeland.[viii] Instability and war in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia jeopardized the safety of ethnic Russian minorities. Without a powerful, centralized state, many Russians felt increasingly vulnerable. These insecurities encouraged a return to a more assertive foreign policy.

It was not the hardliner former KGB agent Putin, but the more liberal-minded Boris Yeltsin and his foreign minister Andrei Kozyrev who first outlined Russia’s right to intervene in the former Soviet Republics. Later dubbed the “Yeltsin Doctrine,” the president articulated this policy in an address to parliament in 1994:

[We must pay] close attention to the problems of the people of Russian extraction living in neighboring states. When it comes to violations of the lawful rights of people of Russia, this is not an exclusive internal affair of some country, but also our national affair, an affair of our state.[ix]

President Putin has since expanded on the Yeltsin Doctrine to legitimize his own interventions within the former Soviet Republics. Notably, the Kremlin’s Foreign Policy Review of 2007 reiterated Russia’s prerogative to “[protect] the rights and legitimate interests of the Russian citizens and compatriots living abroad.”[x] Understanding this humanitarian justification for Russian foreign policy is essential to understanding why children figure so prominently in Russian propaganda narratives.

Russian Portrayals of Children in Ukraine and the Baltic States

Children figure prominently in the Kremlin’s narratives of Ukraine and the NATO-allied Baltic States. Russian state media frequently demonizes Ukrainian and NATO forces through descriptions of violent and perverse acts against ethnic Russian children. In 2017, Russian media propagated a fake-news story detailing a Lithuanian NATO instructor’s rape of two schoolgirls in Ukraine’s separatist Donbas region.[xi] Nor were Lithuanian children themselves safe, according to a report alleging rape by German soldiers stationed in the country.[xii] Violent sensationalist headlines serve as an easy method of inciting indignation among less attentive consumers of Russian news media.

These individual tales of depravity are supplemented by broader, more sustained efforts to malign the governments of Ukraine and the Baltic States. Russian propaganda alleges a deliberate campaign of discrimination against ethnic Russians and their children. Much of this narrative stems from long-standing issues concerning language in the former Soviet republics. Language has been inextricably intertwined with the country’s many internal nationalist movements since the days of the Russian Empire.[xiii] Once free from Moscow’s control, nationalist governments of the newly independent states had greater latitude to promote the revitalization of their languages. Language promotion policies have frequently proved controversial for the countries’ large ethnic Russian populations, who make up roughly 25.6% of the population in Estonia, 28.8% in Latvia, 6.3% in Lithuania, and 17.3% in Ukraine.[xiv] Since 2014, Kiev has revoked the regional official status of the Russian language and declared Ukrainian “as the only means of instruction in schools after the primary division.”[xv] Likewise, the governments of the Baltic states implemented laws to ensure the gradual transition to native-only language education for public secondary schools and do not recognize Russian as an official language.[xvi]

Certainly, complex issues arise from the status of the Russian diaspora, and as Western observers have noted, Ukraine and the Baltic States have less than perfect track records when it comes to their treatment of minorities.[xvii] Yet, Russian propaganda crudely mischaracterizes their policies to exacerbate ethnic divisions. A report in the Russian state news agency Ukraina Ru described Ukraine’s chief language official, Tetiana Monakhova, as a new “speech Fuhrer” who would even fine and punish schoolchildren for speaking in the Russian tongue.[xviii] The report misrepresents Monakhova’s stated policy, which merely fines school officials who refuse to teach in the national language.[xix] Similarly, Russian state media falsely describes recent language reforms in the Baltics as outright “[bans] on teaching in minorities’ languages in schools” and frequently showcases images of protesting children to generate sympathy.[xx] These stories generate anti-government sentiment in the former republics and foment moral outrage in the Russian homeland.

While the tactics may be similar, the goals of Russian propaganda in Ukraine and the Baltic States are distinct. In Ukraine, the Kremlin has focused more on creating humanitarian justifications for its ongoing incursion. Painting Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a humanitarian action has created tangible benefits for Putin and his allies. The invasion was met with resounding approval from the Russian populace: confidence in Putin skyrocketed to 88%, with 83% supporting his handling of relations with Ukraine.”[xxi] Putin utilized this surge in popularity “for purposes of domestic political consolidation.”[xxii] By contrast, the Kremlin’s strategy in the Baltic States seeks instead to galvanize local ethnic Russian support for Russian national parties. These parties serve as a valuable form of Russian soft power in the region, advocating more friendly relations with the homeland.[xxiii] Additionally, the Kremlin seeks to weaken the national unity of the Baltic States, thereby decreasing Western confidence in their leadership.[xxiv] If isolated, the Baltic States become more vulnerable to Russian influence.

Russian Portrayals of Children in Western Democracies

Through the use of children in propaganda, Russian state media paints the West as a land of moral decay. In the infamous “Lisa case,” Russian state media alleged that foreign migrants kidnapped and raped a Russian-German girl. German authorities then “covered up” the case out of “political correctness.” Despite German police disproving the story, the Lisa case was “intensively reported in Russian domestic and foreign media,” leading to organized protests and a public rebuke against Germany by Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov.[xxv] While the Lisa case is the most infamous example, it falls within a greater pattern in which Russian propaganda alleges rampant migrant rape of children and a campaign of conspiracy by European authorities.[xxvi] Additionally, Russian state media accuses Europe of attempting to “legalize pedophilia.”[xxvii] Much like in Ukraine and the Baltic States, Russian propaganda supplements sensational headlines with narratives of systematic abuse towards Russian children in the West. Russian state media and politicians have made repeated false and exaggerated claims over the abuse of adopted Russian children in Scandinavia and the US.[xxviii] [xxix] While not the only tool in Russia’s Western-targeted propaganda arsenal, stories detailing harm to children have been a recurring tactic of the Kremlin in recent years.

Russia’s criticism of Western morality serves three main purposes. First, it fuels xenophobia and anti-establishment sentiment within targeted countries. This serves to foment social unrest and increase vote-share of far-right nationalist parties, thereby weakening Western cohesion.[xxx] Second, these stories contrast the supposed decadence and perversion of liberal democracies with the moral virtues of Russia’s more autocratic, Orthodox Christian system.[xxxi] With the negative example of the West, the Kremlin seeks to foster suspicion against alternative models to autocratic governance. Finally, the Kremlin creates the perception that Russia is surrounded by depraved enemies who harbor irrational hatred for the Russian people. By presenting an external threat, the Kremlin is able to further consolidate its domestic political control. [xxxii] Ultimately, children-based propaganda serves the Kremlin’s agenda of inhibiting Western cooperation and tightening Putin and his allies’ grip on power.

Conclusion

The recurring motif of children in Russian propaganda suggests that the Kremlin recognizes its narrative power over its targeted audiences. By crafting humanitarian narratives around children, the Kremlin has sought to destabilize and cement former Soviet Republics within its sphere of influence, delegitimize alternatives to autocracy, and create divisions in the West. The Kremlin’s increasingly autocratic form of governance and muscular foreign policy have not merely been predicated on nationalist myths and chauvinist expansionism. As evident through its use of children in propaganda, the Kremlin takes advantage of genuine humanitarian concerns in pursuit of its goals.

Nearly a year after Russia’s annexation of Crimea, a propaganda documentary titled “Crimea. The Way Home” aired on Russian television. Featuring high production values and an over two-hour run time, the documentary was one of the Kremlin’s most sophisticated propaganda efforts in recent history. The documentary portrays Putin as a reassuring figure, who, through vigilance and decisiveness, navigated Russia through the crisis. Interspersed among interview footage are scenes detailing the alleged atrocities of Ukrainian nationalists, many of them against children. One scene in particular is quite illustrative. An ethnic Russian man—an alleged member of a self-defense militia prior to Russia’s “rescue” of Crimea—reflects upon his role in the invasion: “all of us are guided by the desire to save our land, and by personal things, including our families.” The man is then shown embracing his wife and daughter as a group of children play carefree before them.[xxxiii] The message of the documentary is clear: Russia’s children—the future of Russia—are under threat. Only through the strong, paternal leadership of Putin can Russia be saved.

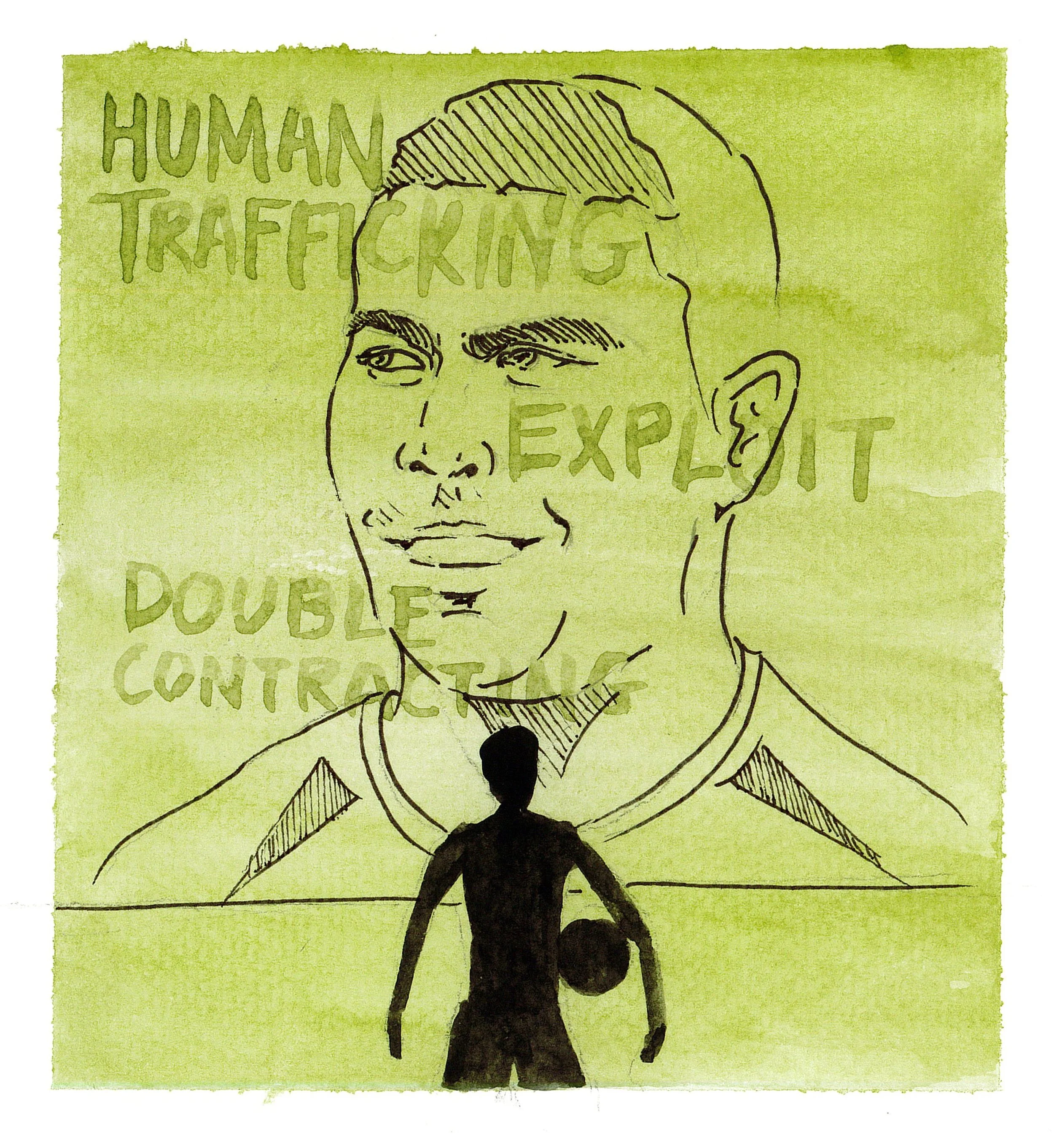

Illustration by Esther Wang

[i] Tetyana Matichak, “Fake: Crucifixion in Slovyansk,” StopFake (blog), July 15, 2014, https://www.stopfake.org/en/lies-crucifixion-on-channel-one/.

[ii] “Russian State TV Says Ukraine Crucifixion Report Possibly ‘Sick Fantasy,’” The Moscow Times, December 21, 2014, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2014/12/21/russian-state-tv-says-ukraine-crucifixion-report-possibly-sick-fantasy-a42519.

[iii] Victoria E. Bonnell, “Iconography of Power: Soviet Political Posters Under Lenin and Stalin,” 1997, 4, https://eds.p.ebscohost.com/eds/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzY5MTRfX0FO0?sid=cc8dc97c-0d79-4511-8360-dd7b4f158594@redis&vid=0&format=EB&rid=1.

[iv] David B. Miller, “Legends of the Icon of Our Lady of Vladimir: A Study of the Development of Muscovite National Consciousness,” Speculum 43, no. 4 (1968): 657, https://doi.org/10.2307/2855325.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Julie K. DeGraffenried, Sacrificing Childhood: Children and the Soviet State in the Great Patriotic War (Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2014), 157.

[vii] DeGraffenried, 161.

[viii] Oncel Sencerman, “Russian Diaspora as a Means of Russian Foreign Policy,” Military Review 98, no. 2 (March 1, 2018): 43.

[ix] Quoted in Teresa Rakowska-Harmstone, “Russia’s Monroe Doctrine: Peacekeeping, Peacemaking, or Imperial Outreach?,” Securitologia 1 (June 1, 2014): 14, https://doi.org/10.5604/18984509.1129693.

[x] Pelnens ed. “The Humanitarian Dimension of Russian Foreign Policy toward Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine and the Baltic States” (CEEPS - Centre for East European Policy Studies, November 10, 2009), 21, http://appc.lv/eng/krievijas-arpolitikas-ekonomiska-un-humanitara-dimensija-attiecibas-ar-baltijas-valstim-ukrainu-moldovu-un-gruziju/.

[xi] “The Pro-Kremlin Pulp Mill,” EU vs Disinformation, September 28, 2017, https://euvsdisinfo.eu/the-pro-kremlin-pulp-mill/.

[xii] Andrew Rettman, “[Investigation] Sex and Lies: Russia’s EU News,” EU Observer, April 18, 2017, https://euobserver.com/investigations/137595.

[xiii] Arto S. Mustajoki, E. I︠U︡. Protasova, and Maria N. Yelenevskaya, eds., The Soft Power of the Russian Language: Pluricentricity, Politics and Policies (London: Routledge, 2020), 13, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9780429061110.

[xiv] Sencerman, “Russian Diaspora as a Means of Russian Foreign Policy,” 43.

[xv] Natalia Kudriatseva, “Ukraine’s Russian-Language Secondary Schools Switch to Ukrainian-Language Instruction: A Challenge?,” Forum For Ukrainian Studies (blog), August 1, 2020, https://ukrainian-studies.ca/2020/08/01/ukraines-russian-language-secondary-schools-switch-to-ukrainian-language-instruction-a-challenge/.

[xvi] Mustajoki, Protasova, and Yelenevskaya, The Soft Power of the Russian Language.

[xvii] “Global Freedom Scores,” Freedom House, 2021, https://freedomhouse.org/countries/freedom-world/scores.

[xviii] Андрей Манчук, “Мовный омбудсман: оштрафуем даже кружки для детей,” Украина.ру, December 11, 2019, https://ukraina.ru/opinion/20191211/1026006316.html.

[xix] Vika Romanyuk, “Fake: Ukraine’s Language Police Will Punish Children for Speaking Russian,” StopFake (blog), December 17, 2019, https://www.stopfake.org/en/fake-ukraine-s-language-police-will-punish-children-for-speaking-russian/.

[xx] Russia Today, “Duma Mulls Sanctions against Latvia over New Law Targeting Russian in Schools,” RT International, April 3, 2018, https://www.rt.com/russia/423044-duma-mulls-sanctions-latvia/.

[xxi] Katie Simmons, Bruce Stokes, and Jacob Poushter, “NATO Publics Blame Russia for Ukrainian Crisis, but Reluctant to Provide Military Aid,” Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project (blog), June 10, 2015, https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2015/06/10/nato-publics-blame-russia-for-ukrainian-crisis-but-reluctant-to-provide-military-aid/.

[xxii] Roy Allison, “Russian ‘Deniable’ Intervention in Ukraine: How and Why Russia Broke the Rules,” International Affairs 90, no. 6 (November 2014): 1291, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12170.

[xxiii] Edward Lucas and Peter Pomeranzev, “Winning the Information War: Techniques and Counter-Strategies to Russian Propaganda in Central and Eastern Europe” (Center for European Policy Analysis, August 2016), 25.

[xxiv] Lucas and Pomeranzev, 24.

[xxv] Stefan Meister, “NATO Review - The ‘Lisa Case’: Germany as a Target of Russian Disinformation,” NATO Review, July 25, 2016, https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2016/07/25/the-lisa-case-germany-as-a-target-of-russian-disinformation/index.html.

[xxvi] Rettman, “[Investigation] Sex and Lies.”

[xxvii] Rettman.

[xxviii] “Children in the Disinformation Spotlight,” EU vs DISINFORMATION, May 3, 2018, https://euvsdisinfo.eu/children-in-the-disinformation-spotlight/.

[xxix] Kathryn Joyce, “Why Adoption Plays Such a Big, Contentious Role in US-Russia Relations,” Vox, July 21, 2017, https://www.vox.com/the-big-idea/2017/7/21/16005500/adoption-russia-us-orphans-abuse-trump.

[xxx] Rettman, “[Investigation] Sex and Lies.”

[xxxi] Rettman.

[xxxii] Rettman.

[xxxiii] Andrey Kondrashev, Crimea. The Way Home. (Vesti News, 2015), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c8nMhCMphYU.