Forgotten and Underestimated: Children’s Role as Positive Contributors in the Peace-Building Process

Forgotten and Underestimated:

Children’s Role as Positive Contributors in the Peace-Building Process

By Gayatri Somaiya

On October 9th, 2012, on a bus coming back from an exam, 15-year-old Malala Yousafzai was shot in the head by a Taliban gunman as retaliation for her gender equality in education activism.[i] Her commitment to the cause, even after a threat to her life, spurred a youth movement across the globe against gender inequality. She challenged the perception that children are immature and weak. Often dismissed as juvenile and powerless, children are frequently shut out of major decisions that potentially harm them. Conflict then further exacerbates children’s lack of agency. However, it is vital to understand the positive role that children can play in political activism and peacebuilding processes since they are going to bear the burden of the consequences of today’s decisions. As Jessica Taft, a leading scholar on youth activism says, “children and youth engage as social, political and economic actors, demonstrating their ability to make social change...to not include children is anti-democratic [and] they deserve to be listened to.''[ii]

How Conflict Harms the Young

Children are directly and uniquely impacted by violence in conflict-ridden areas. In 2019, about 1.6 billion children, or 69% of people under 18, were living in conflict-affected countries. This comes on the heels of a continuous increase in the number of children living in conflict zones since 2000.[iii] What’s more, children are disproportionately affected by conflict. This is due to the changing nature of contemporary conflict, in which casualties are increasingly seen in urban or densely populated areas and there is a blurring of the distinction between civilians and combatants.[iv] In 2019, 24,422 violations were committed against children, an increase of 1,241 from the previous year. These violations included deaths in the family, attacks on schools or hospitals, the loss of education and potential recruitment into armed groups. Such acts were largely carried out by non-state actors. The disproportionality is particularly evident in forced migration, where 40% of the 80 million individuals displaced are children.[v] These impacts of conflict often disrupts the childrens’ ability to build community through traditional avenues, forces them to make decisions that they normally would not have to, and impedes their brain development at critical stages.

In addition to the loss of education and grief of losing family members, children are also recruited to become future perpetrators of violence during times of conflict. Between 2005 and 2020, more than 93,000 children were verified as having been recruited “child soldiers,” though the number is thought to be much higher.[vi] Children can become part of an armed group for various reasons. Some children are coerced or manipulated into joining a group, some are driven by poverty. Others could associate with armed groups for survival, or to be able to protect their communities.[vii] Childrens’ experiences as child soldiers take a heavy toll on their relationships with their families and communities. The varied reasons for joining armed groups indicate that children are not a homogenous group, and have to make decisions that can potentially impact their families and communities in consequential ways.

Violence’s Toll on the Perception of Agency

Children are often shut out of political processes, with suffrage limited based on age. Some could argue that guardians can represent children’s interests. However, while guardians act as proxies for children’s interests, this does not guarantee that children get equal democratic weight given that guardians only get one vote for both their children’s and their own interests. Additionally, guardians might not even let children’s distinct views affect their political decisions. Due to age restrictions on running for office, most political officials are predominantly older adults that do not necessarily represent children’s interests. For example, research has shown that withdrawing from the EU as a result of Brexit could potentially have adverse effects on children and children’s rights, and that children would bear the brunt of the decision. However, the decision-making process has largely remained among adults.[vii] This leads to children not having agency through traditional political processes and having to engage through unconventional means.

Children’s loss of agency is further exacerbated by adults’ perceptions of them in conflict. Children are considered to be a homogenous group that requires protection. They are thought to be more prone to victimization because they are smaller and weaker than adults and because they are dependent on adults for day-to-day care.

Past research has also created perceptions that children’s development can be irrevocably damaged by conflict; however, newer research challenges the perception that conflict always leads to irreversible mental trauma in children.[ix] Social anthropologist Jo Boyden challenges the characterization of war-survival children as traumatized individuals. She argues that there needs to be a paradigm shift which would involve “thinking about children as agents of their own development, who, even during times of great adversity, consciously act upon and influence the environments in which they live.” She argues that children may be more resilient to adverse situations than previously thought, even when they have to negotiate a landscape marred with violence and limited resources.[x] There is also research that suggests that even if children’s development does sustain damage as a result of conflict or violence, their brains remain plastic and are still able to change if they get access to psychological interventions such as positive peace-building processes.[xi]

Children recruited as “child soldiers” are perceived to have even less agency. There is a popular view of violence in which individuals who are perpetrators of violent behavior are considered to have violent personalities, rather than attributing their actions to an individual’s environment or specific experiences at the time. This perception can be more prominent in regards to children as they are considered more impressionable and therefore more likely to internalize behaviors. Once children are coerced into joining these armed groups, they are often considered to be irredeemable based on the presumption that they develop a new relationship to violence that escalates aggressive behavior patterns.[xii] Associating youth with violence makes it hard for children to reintegrate back into their families and communities if and when they escape. Thus, children who have been forced to join armed groups are further excluded from a society that is already less likely to give them a seat at the table.

Other factors of conflict can also reduce a child’s agency. Due to children not having access to conventional methods of getting their voices heard, they often resort to creating communities in educational centers and extracurriculars. For instance, most channels through which children gain community is by being able to go to school. However, conflict can often result in disruption in schooling and other activities such as sports and music groups, which can deny children of other opportunities to communicate with their peers. This can also further exacerbate their exclusion from decision-making processes as being unable to go to school adds to the perception that they are uneducated and hence even more immature.

How Youth can Participate in Political Activism and the Peace-Building Processes

Since children lose agency through the multiple ways, granting them more agency in the peace-building processes would make it easier for them to positively impact political decisions and less likely that they resort to negative community engagement, such as joining gangs or terrorist groups. Peacebuilding is the idea of transforming the structural and cultural conditions that have the potential to generate deadly or destructive conflict. Youth peace-building relies on community building in times of crisis that can not only provide material support, but can empower children and give them a place to belong. As is demonstrated by programs such as youth communities in storm drains, Seeds of Peace, and the CHEM-CHEM group, children are able to play a positive role in peace-building processes through building community, involving themselves in conflict resolution, and empowering other youth through media and cultural activities.[xiii]

In many warzones, youth populations have created and maintained supportive networks and communities. During the 1975 Angolan Civil War, street children created support networks in the storm drains beneath the streets. They shared limited resources and created their own governing ideals. Carolyn Nordstrom, who visited these communities, explained that the youth provided each other with a surrogate family and emotional and economic support, especially when many of these children had lost their parents.[xiv] In Sierra Leone, a dominant girl soldier who was nicknamed “Mommy Queen” protected young girls in an armed group, and it has been reported that she reunited 130 girls with their families after the war was over.[xv] In Bosnia, youth rebuilt a fountain to recreate a historical community place for youth of deeply divided groups.[xvi] All of these examples show how important youth leaders and groups can be for creating positive change and support in war-torn and divided communities.

Children can also be integral in conflict transformation and reconciliation. The NGO Seeds of Peace is dedicated to empowering young leaders from regions of conflict to advance the goal of peace and reconciliation. Seeds of Peace was first focused in the Middle East but has expanded its programming to include young leaders from India, Pakistan and Afghanistan, and now encompasses more than 3500 youth.[xvii] Every summer, hundreds of children engage with each other across lines of conflict in a traditional summer camp program in a manner that would be almost impossible at home. According to their website, their alumni are leading social, economic and political change.[xviii] While this organization is not run by children, it still demonstrates that children can be important in the peace process, especially when they are still too young to experience significant internalized hatred towards another group.

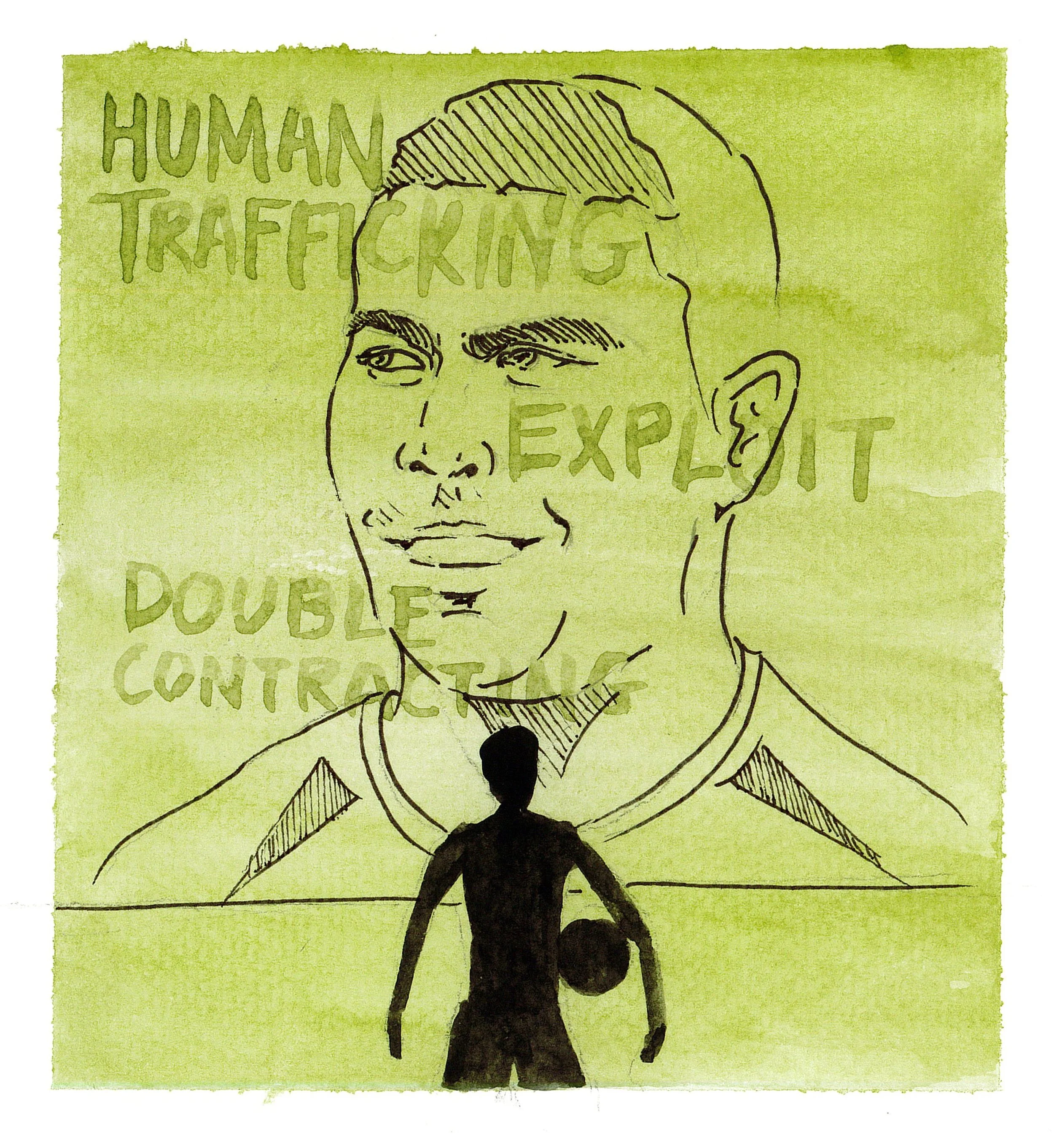

Youth groups can also motivate peers through media and cultural activities. In East Congo, the CHEM-CHEM group is a theater group made up of former male and female child soldiers between 15 and 21 years old.[xix] They use techniques of theatre to raise awareness on topics that are close to youth concerns but also damaging for the community at large, such as rape, war orphans, and sexual exploitation of minors. They perform for young people in schools and youth centers, as well as for entire communities in public places such as local marketplaces.[xx] Often, children who previously fought with armed groups are shunned by their families and communities and left to fend for themselves. Giving them an outlet through cultural activities helps them deal with their trauma and also spread awareness of their experiences.

Conclusion

As more youth groups emerge, it is important to acknowledge the immense positive role that children can play in creating supportive communities during conflict and in creating more peaceful and integrative societies. While children’s protection during conflict should not be minimized, there should also be a growing shift in perceptions of children’s decision making potential so that they can be given more agency and a greater voice in the political processes that will eventually impact them.

Illustration by Esther Wang

[i] “Malala’s Story,” Malala Fund, accessed November 20, 2021, https://malala.org/malalas-story.

[ii] Jennifer McNulty, “Youth activism is on the rise around the globe, and adults should pay attention, says author,” Newscenter, September 17, 2019, https://news.ucsc.edu/2019/09/taft-youth.html.

[iii] Gudrun Østby, Siri Aas Rustad, and Andreas Forø Tollefsen, “Children Affected by

Armed Conflict, 1990–2019,” Conflict Trends, no. 6 (2021): 1. PRIO.

[iv] United Nations Youth “Youth and Armed Conflict,” The United Nations, November 11, 2015.

[v] Catherine Baillie Abidi, “Prevention, Protection and Participation: Children Affected by Armed Conflict,” Gender, Violence and Forced Migration, no. 2 (February 25, 2021). Frontiers in Human Dynamics. https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2021.624133

[vi] “Children recruited by armed forces”, UNICEF, accessed November 20, 2021, https://www.unicef.org/protection/children-recruited-by-armed-forces.

[vii] “Empowerment: Children & Youth: Children, Youth & Peacebuilding Processes,” peacebuildinginitiative, accessed November 20, 2021, http://www.peacebuildinginitiative.org/indexa9e2.html?pageId=2026.

[viii] Helen Stalford, “Not seen, not heard: the implications of Brexit for children,” openDemocracy, June 8, 2016, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/brexit-divisions/not-seen-not-heard-implications-of-brexit-for-children/.

[xi] peacebuildinginitiative, “Empowerment: Children & Youth: Children, Youth & Peacebuilding Processes,”.

[x] peacebuildinginitiative, “Empowerment: Children & Youth: Children, Youth & Peacebuilding Processes,”.

[xi] Jolita Washington, “The Relationship Between Age & Plasticity,” sciencing.com, accessed November 20, 2021, https://sciencing.com/human-skull-growth-6599911.html.

[xii] Boia Jr. Efraime, "The Psychic Reconstruction of Former and Youth Soldiers and Militia," Children, War and Persecution Rebuilding Hope Proceedings of the congress in Maputo, Mozambique, December 1-4, 1996.

[xiii] peacebuildinginitiative, “Empowerment: Children & Youth: Children, Youth & Peacebuilding Processes,”.

[xiv] Carolyn Nordstrom, “Girls and Warzones: Troubling Questions.,” in Troublemakers or Peacemakers? Youth and Post-Accord Peace Building, ed. Siobhan McEvoy-Levy (University of Notre Dame Press, 2005).

[xv] M. Wessells, and D. Jonah, “Reintegration of former youth soldiers in Sierra Leone: Challenges of reconciliation and post-accord peacebuilding,” in Troublemakers or Peacemakers? Youth and Post-Accord Peace Building, ed. Siobhan McEvoy-Levy (University of Notre Dame Press, 2005).

[xvi] Jeffrey Helsing, Namik Kirlic, and Neil McMaster et al., “Young People's Activism and the Transition to Peace: Bosnia, Northern Ireland, and Israel,” in Troublemakers or Peacemakers? Youth and Post-Accord Peace Building, ed. Siobhan McEvoy-Levy (University of Notre Dame Press, 2005).

[xvii] “About Seeds of Peace,” Seeds of Peace, accessed November 20, 2021, https://www.seedsofpeace.org/about/.

[xviii] “Meet some of our seeds,” Seeds of Peace, accessed November 20, 2021, https://www.seedsofpeace.org/seeds/.

[xix] “Congo: Theatre for Reintegrating Child Soldiers,” GlobalGiving, accessed November 20, 2021, https://www.globalgiving.org/projects/congo-child-soldiers/reports/#menu”.

[xx] ibid.